Since the 1990s, policy makers across Europe have promoted product market reforms to reduce costs and improve market efficiency. These reforms most often targeted industries dominated by state monopolies, such as telecommunications, water, and electricity.

Studies have tried to measure how consumers and the wider economy benefit from these reforms, typically comparing their effects on service quality, prices, value added and employment. There has been less attention to their impact in the workplace: How did product market liberalization affect job quality, especially job security and wages? What kinds of jobs were created after the privatization of state monopolies? Were there differences across countries in worker outcomes – and if so, what explains these differences?

We have recently addressed these questions by comparing developments in the telecommunications sector of four European countries: Austria, Denmark, Germany and Sweden. Our findings are based on company publications and 76 interviews with union representatives and employers at the sectoral and at workplace level.

These four countries are often referred to in academic and policy debates as social market economies. They are all thriving capitalist economies that long sustained low wage inequality, thanks in large part to strong traditions of social partnership between well-organized employers’ associations and labor unions. In the telecommunications sector, pay and working conditions were regulated through collective agreements negotiated between these ‘social partners’. They are thus good cases to compare, to ask how industrial relations and labor market institutions filter downward pressure on wages and working conditions from more competitive markets – as well as how those institutions themselves change following product market reforms.

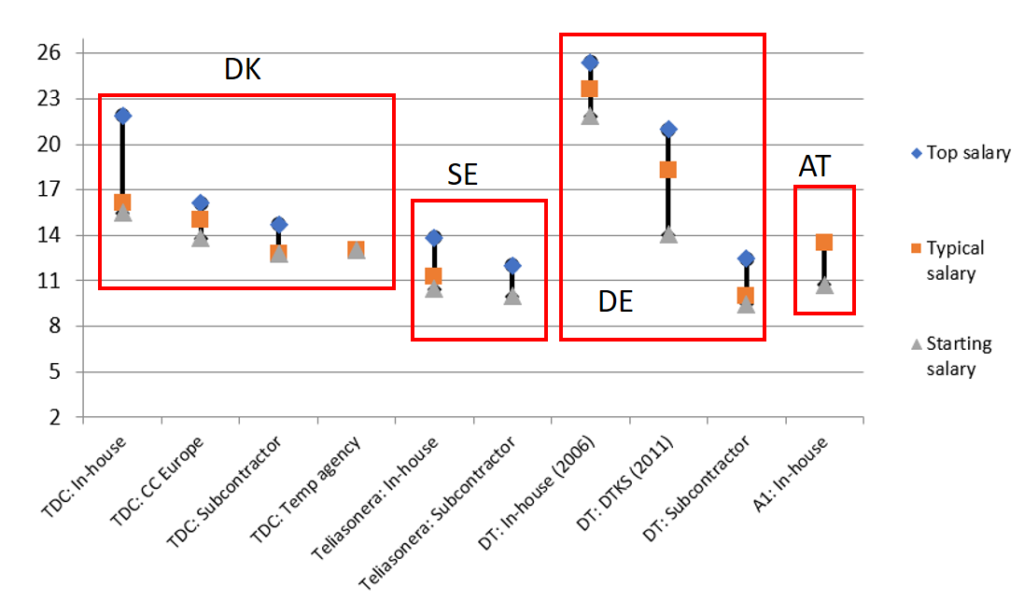

We found substantial variation in the evolution of collective bargaining structures and, as a result, in patterns of wage inequality across our four countries. In Austria and Sweden, unions were able to maintain and extend encompassing collective bargaining agreements across the telecommunications sector. In contrast, telecommunications workers in Germany and Denmark experienced increasingly decentralized and fragmented collective bargaining.

In Austria and Sweden, new competitors were covered by the same industry-level agreements as the former monopolists. When workers or jobs were moved to temporary agencies and subcontractors – for example, companies specializing in call center or technician services – pay and conditions were typically maintained and workers remained under a collective agreement.

In Germany and Denmark, decentralized and fragmented collective bargaining led to growing inequality and downward pressure on pay and conditions as a growing number of employers managed to escape unions altogether.

In Austria, the Union of Post and Telecommunications Employees (GPF) continued to represent employees at the ex-monopolist A1 and its subsidiaries, while the Union of Salaried Employees (GPA) organized employees in new market entrants. While they negotiated two different agreements with the employers’ association in 1997, they had nearly identical pay scales for similar jobs, and their agreements covered all telecommunications employers as well as agency workers.

In Sweden, the two unions representing white-collar and blue-collar workers jointly signed an agreement with TeliaSonera and a sectoral agreement with the employers’ association. These also set equal pay for agency workers and a strong pattern for agreements at subcontractors.

In Germany, by contrast, many new competitors and most subcontractors remained without collective agreements; while the few large companies with agreements – including the incumbent Deutsche Telekom – negotiated only at company level with different unions. Even within Deutsche Telekom, agreements set different salary levels across subsidiaries and subcontractors.

Similarly, in Denmark, the workforce at the ex-monopolist TDC was represented by one union that bargained separate company-level agreements across TDC and its subsidiaries; while agency workers were until recently covered by agreements setting lower wages. Workers at new entrants and subcontractors were represented by the main union HK and other smaller unions, and only partly covered by collective agreements.

As a result, wages for telecommunications workers were more compressed in Austria and Sweden and increasingly unequal in Germany and Denmark.

Figure 1: Comparison of hourly pay levels of call center workers in USD, based on Purchasing Power Parity (2011-12)

Based on our case study findings, we argue that two main factors explain these different patterns of outcomes. First, telecommunications employers in Germany and Denmark were able to find and exploit ‘loopholes’ in national and industry-level institutions to escape agreements or differentiate pay and conditions for similar employee groups.

For instance, in Denmark telecom companies could apply the most convenient agreement signed by one of the two employers’ associations, and unions were restricted from using boycotts and strikes against service employers who had less than 50% union membership. In Germany, the extension of collective agreements to the whole sector by law could take place only if bargaining coverage was at least 50 percent of the workers in the sector concerned, and the extension was judged to be in the public interest and supported by a special collective bargaining committee.

In contrast, in Austria and Sweden there was only one employers’ association signing the collective agreement for the whole sector; with membership of that association mandatory in Austria.

Second, different patterns of inter-union cooperation or competition affected unions’ ability to bargain encompassing collective agreements. In Austria and Sweden, there was a clear division of responsibility between the unions, which therefore did not compete for members. In Germany and Denmark, there was significant inter-union competition, which was exacerbated by a bargaining structure in which most agreements were at company-level and firms could easily move work between different collective agreements with different unions.

These two factors were connected in positive or negative feedback loops: prior loopholes exacerbated inter-union competition; while inter-union cooperation was necessary to develop coordinated strategies needed to close emerging loopholes. The presence of a strong and united labor front in Austria and Sweden prevented employers from leaving encompassing agreements, while inter-union competition in Germany and Denmark made it much more difficult for unions to work together to develop new coordination or extension mechanisms.

Our study gives insights into the conditions under which social solidarity can be constructed or maintained despite liberalization and privatization. Even though it focuses on one sector, findings support the argument that unions and collective bargaining are crucial for preventing growing wage inequality in increasingly competitive markets.

No Comments