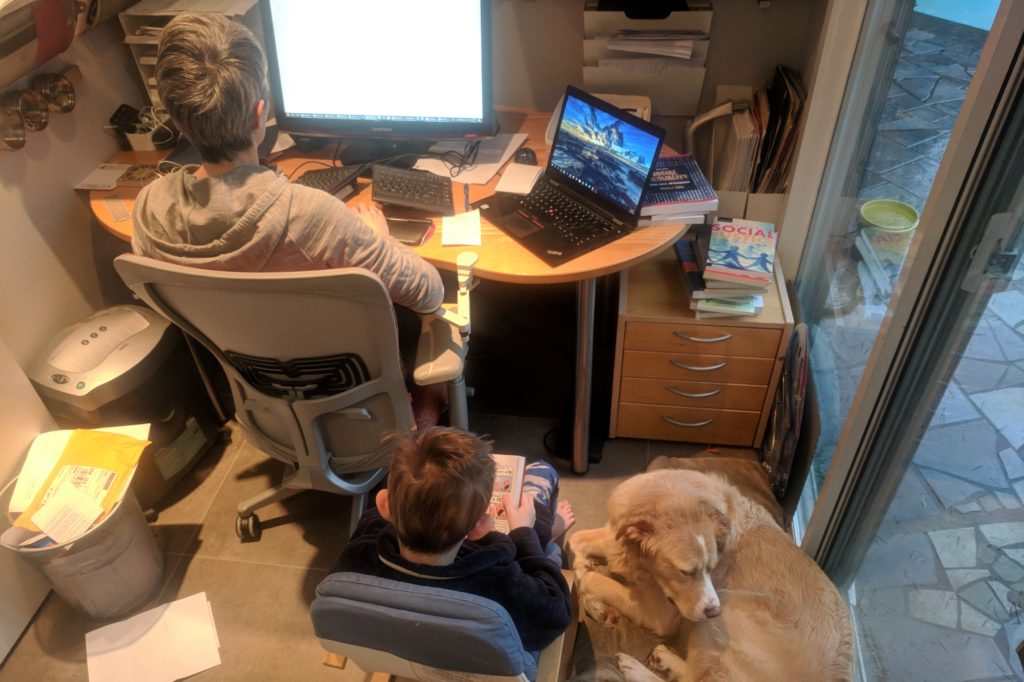

For many families, integrating work and care remains a challenge. Is flexible work the answer? By affording workers greater freedom to organize their jobs in ways that suit their lives, flexible hours and the ability to work from home can help parents meet children’s needs while still getting their work done.

For many families, integrating work and care remains a challenge. Is flexible work the answer? By affording workers greater freedom to organize their jobs in ways that suit their lives, flexible hours and the ability to work from home can help parents meet children’s needs while still getting their work done.

A puking child is never fun, but it doesn’t have to mean missing out on the day’s work. Daughter needs to be picked up from daycare at 5 sharp? No problem, start the workday earlier to compensate or finish it at home.

Since mothers still do most of the heavy lifting around caregiving, reducing work-life conflict could also help equalize their opportunities in the workplace. But is there a dark side to flexibility?

In our recent study, we investigate how flexible work arrangements – including flexible hours and working at home – impact wage gaps between otherwise similar mothers and childless women in Canada. Does flexibility enhance mothers’ capacity to accommodate work and family demands – or do mothers who access flexible arrangements pay a price in their wages?

The concern is that rearranging work to accommodate the demands of care can violate deeply held assumptions about what it means to be an ideal worker. Rather than help mothers at work, flexible work arrangements may stigmatize them as less committed to their jobs, strengthening negative stereotypes that contribute to motherhood pay penalties. Mothers may also be re-routed to less demanding work or encouraged to accept jobs that are otherwise less desirable (e.g. downshifting to a position with lower pay) to access flexibility.

The good news for work-family integration is that, overall, we find that flexibility helps more than it hurts. Average wage gaps between mothers and childless women are much smaller when workers have flexible hours and when they shift some of their regularly scheduled paid hours from the workplace to home.

The motherhood pay penalty is eliminated entirely among workers who bring additional unpaid work home.

Does flexible work matter more for wage gaps within or across firms?

One of the virtues of our Statistics Canada survey data, which links workers to their workplaces (a representative sample of workplaces is sampled, then workers within each workplace are sampled), is that it not only allows us to see the overall impact of different forms of flexibility, but also allows greater clarity about the pathways through which (dis)advantages accrue.

In particular, we can tell whether flexible hours are shifting wage gaps between workers in the same firm, or if they matter because they shape the distribution of mothers and childless women across better and worse-paying firms.

We find that flexible hours help mothers in part by reducing motherhood wage gaps within workplaces. But this turns out to be a fairly minor factor. Far more important is the fact that flexible hours reduce barriers to mothers’ employment in better paying establishments.

While the positive impact of bringing extra unpaid work home is stronger within workplaces than for flexible hours, it also works chiefly by improving mothers’ access to better paying firms.

Thus while having flexible work hours and being able to bring overload work home may help even the playing field within organizations, this isn’t its key benefit. When work is organized more flexibly, barriers that shut mothers out of better paying firms drop. This suggests that flexibility helps allay employers’ concerns – or stereotypes – about mothers’ ability to handle more rigidly-organized or demanding jobs.

Things are a little different for those substituting paid work time at home for hours in the workplace. This form of spatial flexibility helps mothers chiefly by reducing within-workplace wage gaps. This may be the answer to the sick kid problem: allowing mothers to substitute some work at home for regular paid work hours would allow them to keep pace with their childless coworkers when they can’t be in two places at once.

Educational differences

We also examined differences in the benefits of flexibility for mothers of varying educational levels. After all, the ability to re-arrange work in more flexible ways varies a great deal across jobs (a server cannot easily work from home), as does the ability to afford reliable childcare arrangements, and norms of work and family devotion.

Do mothers in the most demanding jobs benefit most from flexibility, or is it most advantageous for those who face rigid schedules, and more precarious work and care arrangements?

It turns out that flexible hours help mothers much more as education levels rise. This suggests that it is the opportunity to better accommodate a more demanding paid work load, characteristic of managerial and professional jobs, that matters most in this case.

However, highly educated women do not benefit most from all forms of flexibility. Indeed, substituting working hours at home for time in the workplace dramatically increases motherhood wage gaps for the most educated.

This is particularly interesting in light of the fact that childless women in this educational group are equally likely to take advantage of this type of flexibility, which should minimize its stigmatizing association with work-family accommodation.

The fact that we find penalties for this type of working at home for highly educated mothers suggests that face time remains a key indicator – whether real or perceived – of productivity in high status jobs.

At the other end of the educational spectrum, bringing extra unpaid work home is associated with larger motherhood wage gaps for women with a high school education or less. Whether taking on such extra work reflects heightened vulnerability among the poorest compensated and least educated mothers is an important question for future work.

To reduce motherhood pay gaps don’t change mothers – change the workplace

Overall, our findings suggest that flexible work arrangements are a promising route to not only improving work-life balance, but also easing some of the disadvantages faced by mothers in the workplace.

However, they also highlight the importance of remaining attentive to women’s social class positioning, and not presuming that particular “family friendly” work arrangements will have consistent implications for all women in all jobs.

Nevertheless, our research underscores the importance of altering workplace arrangements – including access to flexibility – to better enhance mothers’ work-family facilitation and chip away at glaring motherhood pay penalties.

No Comments