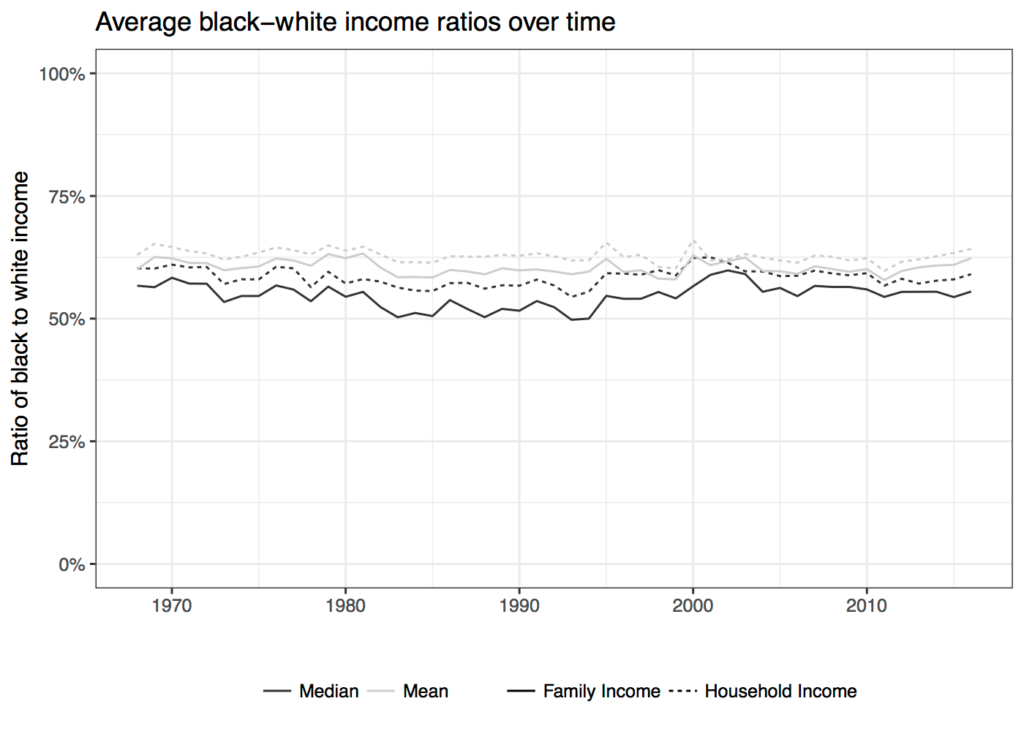

Fifty years after the civil rights movement, racial economic inequality remains a major fact of American life. In fact, the gap in family income between blacks and whites has been almost perfectly constant since the 1960s.

Fifty years after the civil rights movement, racial economic inequality remains a major fact of American life. In fact, the gap in family income between blacks and whites has been almost perfectly constant since the 1960s.

In a recent study, I show that the persistence of the racial income gap results from two opposing trends. Over the last 50 years there has been real if incomplete progress towards racial equality in income ranks negated by the national trend of rising income inequality overall.

In 1968, just after the Civil Rights Movement, the median African American had family income 57% that of the median white American. In 2016, the ratio was 56%. The utter lack of progress is striking.

It’s also a bit puzzling, because real efforts were made to reduce discrimination in employment and equalize access to education and other resources needed to succeed in the United States.

Racial gaps in many other social outcomes have contracted since the 1960s: college attainment, high school test scores, and life expectancy have all seen some convergence between blacks and whites, though progress is by no means complete. So why has there been so little progress towards equalizing incomes?

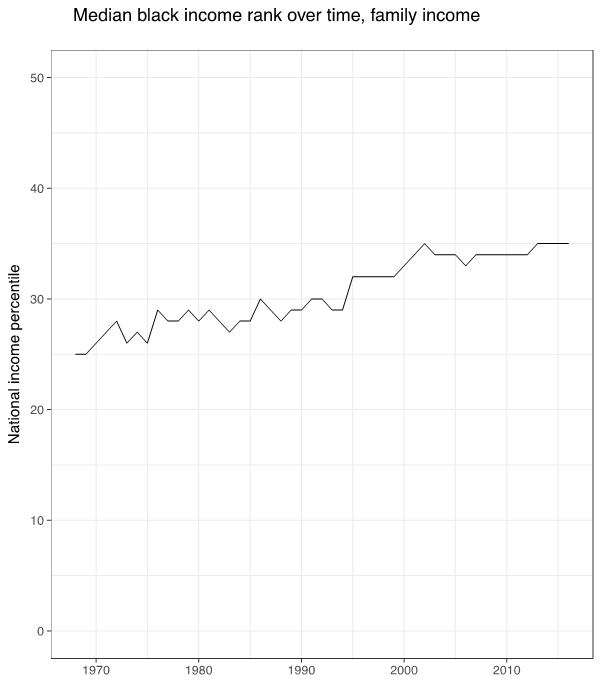

It turns out that the intransigent racial income gap is the result of two opposing trends. On the one hand, blacks have made real progress climbing to higher positions on the income distribution.

From 1968-2016, the median African American climbed from the 25th percentile of the national income distribution to the 35th. While this progress is by no means complete, it was enough to narrow the gap in income ranks between blacks and whites by almost a third. In the 1960s the large majority of whites earned more than the typical black person. By 2016 that proportion had shrunk substantially.

This progress came despite continued racial disparities in parental wealth, access to educational resources, and treatment in the labor market.

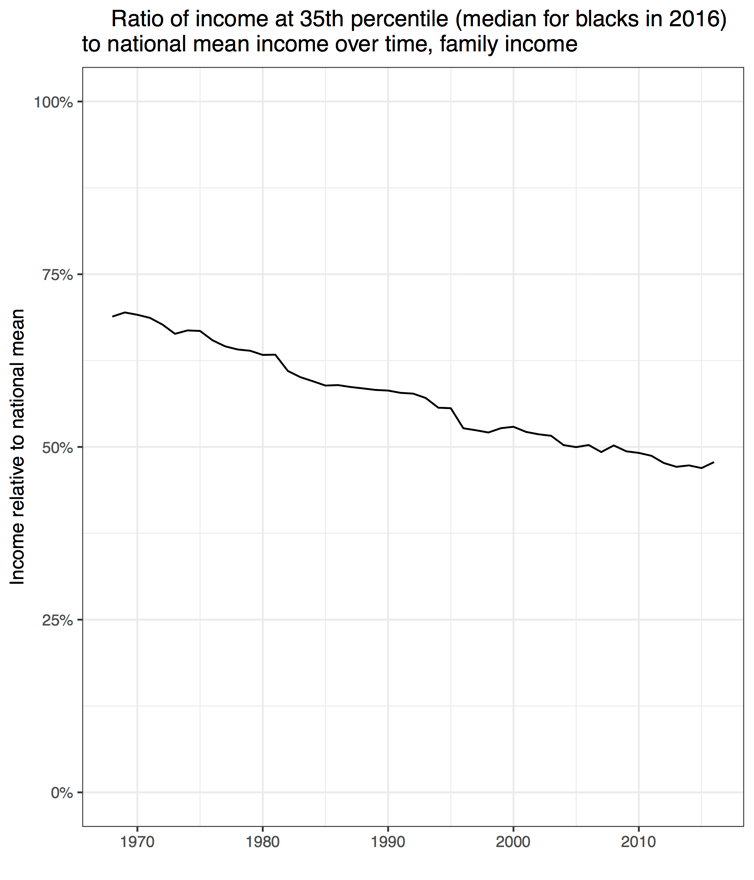

Yet just as African Americans were entering its ranks in large numbers for the first time, broader economic forces were undermining the financial security of the middle class.

Starting in the 1970s, changes to the economy and to public policy began concentrating a larger and larger share of national income in the pockets of the richest members of society. Incomes for the middle class and the poor have stagnated: after adjusting for inflation, the average incomes of the poorer half of society actually shrunk from 1968 to 2014, while incomes for the richest 1% almost tripled.

These changes to the income distribution meant that reaching the middle class didn’t mean the same thing for African Americans as it did for social groups that climbed the income ladder earlier in US history.

To see this, consider the income earned at the 35th percentile, where the median African American stood in 2016. In 1968, a person at the 35th percentile had an income 69% of the national mean. But by 2016, income at the 35th percentile had fallen to be just 49%. Because of rising inequality, successfully reaching the middle of the distribution did not provide the same economic reward to blacks as it had to previous groups of Americans.

We can see the effect of rising income inequality on racial disparities by simulating what the income gap would look like if the overall income distribution had stayed constant. If overall inequality hadn’t gone up, the ratio of median black to white family income would have climbed from 57% to 70%, decreasing the racial income gap by 30%. That would still be a long way from racial equality, but much closer than we are now.

Of course, rising inequality has hurt Americans of all races: even for whites, the median income has declined by 14% as a share of the national mean. But because African Americans remain overrepresented among the poorer segments of society, economic shifts that have harmed almost everyone have also increased the average gap between blacks and whites. These shifts were strong enough to undo what would otherwise have been substantial, though certainly incomplete, progress towards racial equity in terms of income.

These findings demonstrate how economic inequality and racial inequality are fundamentally intertwined. During the last 50 years, a fairly large improvement in the relative position of African Americans was entirely undone by national economic shifts with no superficial connection to race. Going forward, high levels of overall inequality will make it harder to achieve racial parity, since any improvement in relative terms means less in terms of dollars.

On the other hand, these results show how policies to make the economy more equal in general will also contribute towards equality between races—a point many civil rights leaders and academics have made over the years. The vast majority of Americans have an interest in reversing wage stagnation and making the economy more equitable. Progress on that front will also reduce the gaps between racial groups.

No Comments