Feminism provides a vital but surprisingly marginalised resource for researchers interested in the sociology of work, organizations, and management. We have come to this conclusion in part through our experiences of conducting feminist research on workplaces, and in part through guest editing a newly published special issue of the journal Human Relations that focuses on feminist analysis of social relations in organizations.

In addition to theoretical insights that enable us to make sense of, and challenge, gendered inequality, discrimination, violence, and oppression, feminism, in all its diverse forms, provokes thought on how to challenge and change all exploitative social formations. As Jacqueline Rose recently suggested in Women in Dark Times, feminism asks unique questions as a way of ‘seeing through what is already crazy about the world, notably the cruelty and injustice’ (Rose, 2014: x) of everyday lives. As Amanda Sinclair has also made clear in her recent embodied feminist memoir of an academic working life which concludes the Special Issue, feminism can also provide unique ways of responding to those questions, both theoretically and methodologically.

We find this marginality in our field of organization studies puzzling.

Feminist movements have contributed towards major social, economic and educational change as a consequence of raising issues of gender equality and gendered oppression in many parts of the world. The list of achievements is striking in its length and social significance. Legal rights to equal pay, education, and access to professions (including politics) and independent property ownership are the most prominent social changes instigated through feminism.

Clearly, progress in these areas has been uneven. The United Nations Gender Inequality Index shows that powerfully discriminatory conditions persist in countries such as Saudi Arabia, Liberia, Afghanistan, or Uganda. Women’s bodies are central to this, as markers of difference, but also, increasingly, women’s pride in being able to make change happen. Research in organization studies is finally recognising this as more central, in part through recognising that our most prestigious journals publish very little feminist analysis.

Feminist research in organizations provokes thought on experiences and issues that have little or no place in the conventional textbooks we work with in organizational behaviour classes. Pregnancy and menopause, for example, two uniquely female and relatively common experiences, provide the base for analyses that show how women negotiate disciplinary organizations and neoliberal managerialism.

Astrid Huopalainen and Suvi Satama draw on matricentric feminism in their work to suggest that social privilege can allow pregnant women to navigate the demands of neoliberal work environments and the performative pressures associated with discourses of ‘new motherhood’. Further along the embodied continuum, Gavin Jack, Kathleen Riach, and Emily Bariola analyse what they term ‘menopausal subjectivities’ via their temporal modalities, to emphasise that embodiment at work unfolds through a complex co-evolution of biological and cultural conditions.

These Special Issue two papers are remarkable in the new ground that they map in feminist understandings of social relations at work. In our field of organization studies, feminism has historically been marginalised and excluded from the most prestigious journals that define what the academic community collectively considers to be legitimate and relevant research. Consequently, feminist methodologies, analysis, and theory are less prominent than other ways of analysing organizations critically, such as post-structural perspectives or Critical Theory.

This exclusion and marginalization appears to be greater than in other disciplines, including close cognate areas such as organizational communication studies. As Karen Lee Ashcraft observes, that field welcomes feminism as a mainstream approach, perhaps even as a dominant perspective.

The exclusion of feminism from research that addresses issues related to the workplace becomes even more remarkable when considered alongside the current articulation of feminist thought and activism that substantially focuses on exposing and shifting patriarchal power relations in economic institutions and organizations. Prominent examples of this activism include the Everyday Sexism Project (ESP), started by Laura Bates in the UK, which collates women’s experiences of gendered harassment and violence from around the world, including many stories that concern workplaces. As Sheena Vachhani and Alison Pullen observe in their timely analysis of ESP, it provides a grassroots forum for public resistance to sexism and harassment, creating a sense of what Clare Hemmings calls ‘affective solidarity’, built on practising politics of experience and empathy.

ESP and many other movements show that feminism belongs at the centre of organization studies. The globally recognized #metoo movement documents the practices of sexual harassment and assault that still prevail in many industries, such as film-making.

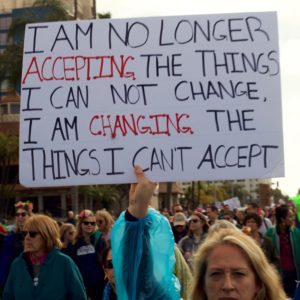

The rise of new feminist social movements in the political sphere also raises questions about the significance of feminism in activist organizations. Recent Women’s Marches provoked by the 2016 US presidential elections are interpreted by Melissa Tyler as creating a radically different embodied ethics of co-presence that enables a more political form of inclusion.

In another, but equally discriminatory and damaging context, the lived experience of women achieving status and success as ‘neoliberal executives’ is the primary focus of Darren Baker and Elizabeth Kelan’s recent work. Their psychosocial analysis is unsparing in how it shows how this small cadre of women uphold the neoliberal ideal, alongside the psychic efforts required to do so.

These recently published papers all show that feminism asks singular questions of women’s working lives and have implications for the totality of social relations at work. Feminism is also unique in that it provokes both thought on and change in contemporary workplaces, through defining problematics and puzzles for those inhabiting them and for those of us researching them. Feminism, in its many forms, deserves a stronger voice and a more secure place in how we make sense of management, organization and work.

Read more

Emma Bell, Susan Meriläinen, Scott Taylor, and Janne Tienari, “Time’s Up! Feminist theory and activism meet organization studies,” Human Relations 2019.

Image: Bonzo McGrue/Women’s March 2017 San Diego CA, via Wikimedia Commons CC-B-Y-2.0

No Comments