Spoiler alert: plot/character details and research-based social analysis ahead.

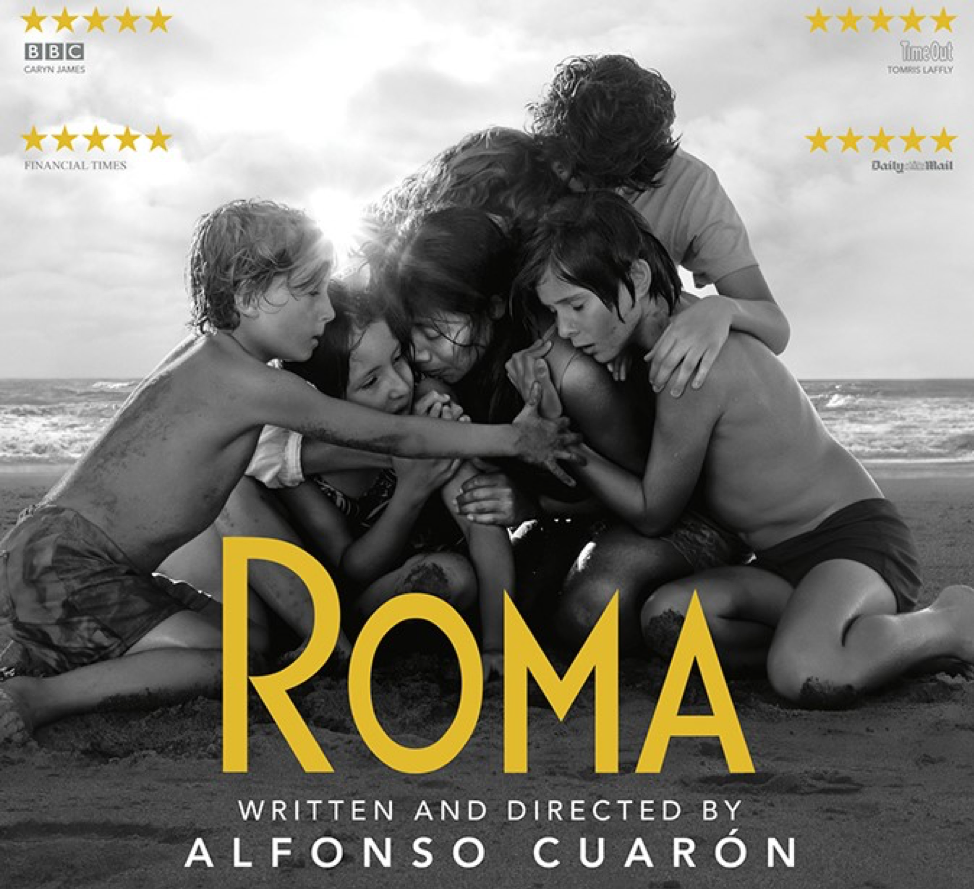

The film Roma, written and directed by Academy Award winner Alfonso Cuarón and chronicling a year in the life of a domestic worker and the family that employs her, was released in theaters and on Netflix in 2018. On the heels of several recent award wins (Golden Globe for Best Picture and Best Director; BAFTA for Best Film and Best Director; Directors Guild of America for Best Director), Roma is among the favorites to win big at the Oscars this month.

In addition to the critics’ adulation, Roma has inspired conversations among the public and has been strategically used by domestic worker organizations to heighten their visibility. But the voices of researchers who study domestic work in Latin America have been missing from these conversations.

As the founder and coordinator of a research network, RITHAL (Red de Investigaciones sobre el Trabajo del Hogar an América Latina – Network of Research on Domestic Work in Latin Amerca), I feel strongly that we can make valuable contributions to public discussions of the film.

About 27% of the world’s domestic workers live in Latin America. As in other parts of the world, this occupation is often the last resort for women from poor or rural backgrounds with low levels of education. While research and popular culture portrayals in English often focus on international migrant domestic workers, it is more common for Latin American domestic workers in countries such as Mexico to be internal migrants, as reflected in Roma.

Over the past several decades, domestic workers have been organizing to claim their labor rights, bringing awareness to poor working conditions, illegally low salaries, and lack of benefits such as social security, maternity leave, and overtime pay. While more and more countries have laws protecting domestic workers’ rights, enforcement tends to be nonexistent or at best sporadic, reinforcing longstanding patron-servant relationships in which employers dominate, degrade, and exploit workers they see as inferior.

Even domestic workers who have positive relationships with their employers experience stigma and discrimination due to their occupation, an aspect of domestic work that is absent in the film.

The following four essays, from researchers who investigate domestic work in historical and contemporary Latin American settings, bring new voices into the public conversations about Roma.

Séverine Durin, the foremost expert on indigenous domestic workers in contemporary Mexico, writes about how domestic workers both embody motherhood as they care for other people’s children, and simultaneously miss out on the chance to be mothers themselves.

Leda Pérez, who conducts research on domestic work in Peru, shows how the film, despite having a main character who is a domestic worker, denies her a rich interior life and consciousness, still privileging the employers’ point of view.

Simca Simpson Lapp, who studies implementation of domestic work regulation in Uruguay and Argentina, examines the limits of fictive kinship between employers and domestic workers, who also need care and may provide unpaid care to their own families.

Karina Vásquez, who specializes in historical and media representations of domestic work in Argentina, discusses how the film’s romanticizing of domestic workers’ relationships with the families that employ them covers over the exploitative aspects of the work.

No Comments