It is clear from research on corporate leadership that a glass ceiling prevents many women from occupying top executive or CEO positions.

In a recent article, we find that the glass ceiling is far more extensive than previous literature finds: women are not just excluded from top leadership positions, but rather they are excluded from nearly all top income positions regardless of occupation. We also find that progress on this front has been stalled for the last twenty years.

Scholars and journalists have paid increasing attention to people at the top of the income distribution, such as members of the top one percent, because they control significant financial resources. For example, our calculations from the 2016 Survey of Consumer Finances show that top one percent households receive nearly a quarter of all US income.

We also find that it takes at least $845,000 in household income to be in the top one percent. This concentration of income is particularly troubling given that members of the top one percent not only have disproportional financial resources, but they also exercise considerable political and social power.

Although top income earners are attracting more attention, the focus is typically at the household level. That is, discussion of top households tends to focus on differences between top one percent households and the remaining 99%. While this work is critical for understanding inequality among households, conceptualizing the rich at the household level obscures whose income—men’s or women’s—leads to a household being in the top one percent.

Because individuals who are in the one percent based on their own income (i.e., without including their spouse’s income) likely accumulate more social, economic, and political power than their spouse, it is critical to distinguish how gender matters in these households.

In our study, we examine the extent to which women’s income contributes to a household’s one percent status and the pathways associated with men and women making it into the one percent. Specifically, we examine whether women’s own employment characteristics and education provide a personal pathway to one percent status based on their own income or whether women primarily have one percent status via marriage because of their spouse’s income.

We use data from the 1995–2016 Survey of Consumer Finances (SCF) to study these ideas empirically. The Federal Reserve Board’s SCF is a nationally-representative, cross-sectional survey conducted every three years, and provides highly accurate information on top-income households.

The one percent glass ceiling

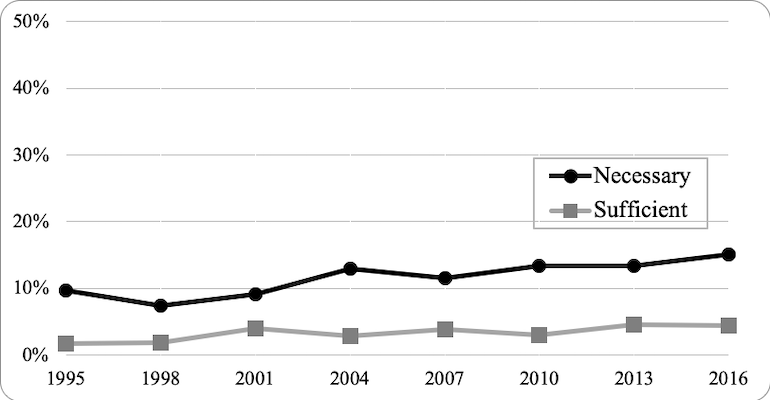

The findings are stark. We find that married households rarely qualify for one percent status based on women’s income alone. Specifically, Figure 1 shows that women’s income alone was sufficient for one percent status in less than 2% of elite households in 1995; the corresponding statistic was still only 4.5% in 2013 and 2016.

We also find that women’s income is rarely necessary for married households to meet the one percent threshold. Figure 1 shows that women’s income was necessary in about 9.6% and 7.4% of married one percent households in 1995 and 1998, respectively; in 2016, the percentage had climbed some but nevertheless remained low at 15%.

Together, these findings indicate that men’s income largely determines a household’s one percent status because most households would have one percent status regardless of women’s income. Broadly, these findings indicate a clear male dominance of income resources in families in the upper echelon.

Of course, a minority of women do enter the one percent as a result of their own personal achievements. We find that having higher education and being self-employed increase women’s likelihood of qualifying for one percent status based on their own income. In fact, self-employment carries a significantly higher return for women than for men in earning elite-level income.

For example, women who are self-employed have 30 times higher odds of earning top one percent income than non-self-employed women, but men who are self-employed have only 9 times higher odds of earning top one percent income than non-self-employed men, a gender difference that is statistically significant.

This, of course, does not imply that self-employed women have higher rates of personal one percent status than self-employed men (they do not as we also show in our article); instead, it implies that women may need self-employment more than men to reach this elite position.

Our findings reflect the fact that women who are not self-employed have virtually no chance of personally qualifying for one percent status on their own; thus, self-employment is likely women’s only viable route to earning elite-level income.

Self-employment (via starting a successful business) may free ambitious and competent women from biases and discrimination that otherwise hinder their upward mobility in corporate America, despite the reality that women still face gender-based hurdles related to business startup and growth. Given that men hold most high-income financial (e.g., hedge fund managers) and leadership positions (e.g., CEOs), men have routes other than self-employment to reaching personal one percent status (even though self-employment is still an important pathway for men as well).

Although higher education and self-employment are important for women’s own economic mobility, we find that women’s main route to one percent status is via marriage when their husband’s income is included in the household income total.

Specifically, married women are 992% more likely to be part of a one percent household than single women, holding constant other important characteristics (e.g., race, education, age). Married men are also more likely to have household one percent status than single men (71% more likely), however, the positive association is not nearly as strong for men as it is for women.

Clearly, women benefit from marriage by gaining access to their spouse’s income. But why is there a positive association between men’s household one percent status and marriage? Two potential explanations exist, which future research should confirm.

First, as research on general household populations show, marriage tends to provide men access to their wives’ unpaid labor, which frees men to devote more time to work and take risks with their careers. Second, selection effects are likely at play: the characteristics that make men more likely to financially succeed (and push a household into the one percent) also make them more likely to marry.

Importantly, we find that not all married women have similar chances of making it to a one percent household. Rather, there are clear differences among married women in access to elite income positions: married women who have highly educated or self-employed husbands are best positioned to be in an elite household.

Considering that men’s income mostly determines a household one percent status, men’s membership in a top one percent household is less strongly tied to their spouse’s characteristics. Ultimately, this highlights the different and unequal pathways associated with men’s and women’s access to these elite positions.

Progress over time?

Our work shows that women are clearly less likely than men to earn elite-level income, but has this female disadvantage decreased over time? Although the statistics shown in Figure 1 seemingly suggest some gender gains, when we use more rigorous methods and control for important factors (age, education, etc.) we find that women have not made any gains over the past 20 years in closing the gender gap in earning top one percent income. Their chances of earning elite-level income, relative to men, are the same today as they were in the mid-to-late 1990s.

How is this possible? Women now own one-third of all US businesses, and graduate from MBA, MD, and JD programs in comparable numbers as men. They also represent nearly half the workforce in the United States. Despite these gains, the federal government has made no major legislative changes to reduce work/family conflict over the past twenty years, conflict that more frequently negatively affects women’s careers than men’s.

Moreover, although more women own businesses today, the revenues earned by female-owned have barely increased in recent decades; similarly, women continue to employ far fewer employees than male-owned businesses. Perhaps most striking, high-income women have made the least amount of progress in closing the gender gap over the past few decades, such that the gender gap is now largest among high-income workers compared to all other socioeconomic classes. This is partly because occupational segregation among men and women remains stark, in which women have made few inroads into exceptionally high-paying occupations.

Broader implications

Our research suggests that the glass ceiling is more expansive than previously thought. Women not only face barriers accessing leadership positions, but they also experience difficulty accessing all top income positions. This has broad implications because people in the one percent have significant influence over our political system and they wield substantial economic power through major business decisions and donations to community organizations.

Women may be part of many married one percent households, but until they gain parity in income resources, men will likely continue to exercise the majority of substantive power within this group.

Read moreRead More

Jill E. Yavorsky, Lisa A. Keister, Yue Qian, and Michael Nau. “Women in the One Percent: Gender Dynamics in Top Income Positions.” American Sociological Review 2019.

Image: Jenifer Corrêa via Flickr (CC BY 2.0)

No Comments