One of the most vexing political and social science problems is the persistence of the gender wage gap. In a recently published article in the American Journal of Sociology, we argue that looking at an organization’s choices is crucial to understanding the gender pay gap. Studies that focus on pay as a result of individual worker choices (such as assuming women choose lower paying jobs to accommodate family) are missing that organizations also make choices about pay.

Our article offers a new approach to analyzing the gender pay gap, examining how different organizations pay women less than men using multiple mechanisms at the organization level. These organizational-level processes are often hidden, and harder to see than individual choices, but may be more powerful.

Because we were looking at workers in the federal government in the US, initially we assumed that the federal general schedule (GS)—the system of pay grades tied to job requirements, responsibilities, education, and tenure—would effectively reduce most pay inequality between similarly qualified workers.

What we actually found were pay gaps that declined over time but persisted, and that different organizations had different patterns of gendered outcomes. How the organizations used, or did not use, the GS was an important mechanism producing some of those gendered outcomes.

We were surprised by one of the more hidden mechanisms for the gender pay gap in US federal science agencies. We looked at different mechanisms that have been identified in the research literature on gender pay gaps—such as segregation of women into lower paying jobs, or more direct discrimination where men are paid more than women in the same jobs.

What we didn’t expect to see was some federal agencies choose more often to pay men, rather than women off of the GS pay grades, and pay those off-grade men higher average salaries. We would have missed this hidden inequality mechanism if we had not obtained agency-level data for the population of US federal government workers.

We use a database that includes virtually every federal worker from 1994 to 2008. Before we received the data, records were de-identified by the Office of Personnel Management (OPM). Our database includes over 16 million observations on public sector employees, linking employees to the agencies in which they work.

Embedding employees in the agencies in which they work means we know which organization and location and job that workers hold, and can compare equivalent men and women workers—in the same jobs in the same workplaces, and controlling for their education and experience, and race. Often gender pay gap research is faulted for comparing apples to oranges (say, women servers in diners to men servers in fine dining restaurants); our study compares apples to apples—women and men working in the same establishments with detailed information on their jobs and pay.

The analysis for this paper focused on seven U.S. science agencies that span physical, biological and engineering disciplines, as well as interdisciplinary research: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), National Institutes of Health (NIH), Department of Agriculture (USDA), National Science Foundation (NSF), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), and Department of Energy (DOE).

Our research indicates that the resulting pay gaps between men and women at the science agencies we studied are associated with the culturally framed “gender” of the agencies’ fields of research.

In the agencies based on physical sciences and engineering – the sciences culturally framed as more masculine – we found that more of the pay gap can be attributed to within-job discrimination, so that men are paid more than women in the exact same jobs at the same agency, at the same pay grade and with the same work experience. This pattern was more evident at NOAA and DOE.

In the agencies based on more gender-neutral sciences, such as life sciences and interdisciplinary agencies, we found that more of the pay gap can be attributed to how organizations choose to sort individuals, both into jobs and onto different pay scales. Men and women of different educational and racial backgrounds are hired into different jobs in these agencies in a way that reinforces traditional hierarchies, but does not produce much within-job discrimination.

In addition to the differences between the gender-neutral and masculine science agencies in what explains gender pay gaps, we found a striking range of variation at individual agencies. Differences in how agencies sort workers by their individual characteristics, for example, account for approximately 84% of the gender pay gap at the NSF, compared to only 47% at NOAA. Meanwhile, occupational segregation—how male or female dominated different occupations/GS ranks are—accounts for about 33% of the gender pay gap at the USDA, compared to less than 9% at the NSF.

Our research shows the importance and value of this type of systemic, periodic collection and analysis of employer level pay data. The EEOC is working toward this kind of reporting within the private sector under new reporting guidelines that began September 30, 2019.

With the new data to be collected, employers and the EEOC can get a better handle on organization level pay gaps and potential causes. Our research provides a model for how to do just that.

Moving beyond individual level enforcement mechanisms is key. First, organizational level data on gender, race, and other employee characteristics need to be gathered systematically and periodically. Next, the data need to be monitored for pay gaps and mechanisms causing those gaps. Organizational level perspectives are a critical part of addressing persistent gender disparities.

Read more

Laurel Smith-Doerr, Sharla Alegria, Kaye Husbands Fealing, Debra Fitzpatrick, and Donald Tomaskovic-Devey. “Gender Pay Gaps in US Federal Science Agencies: An Organizational Approach.” in American Journal of Sociology 2019.

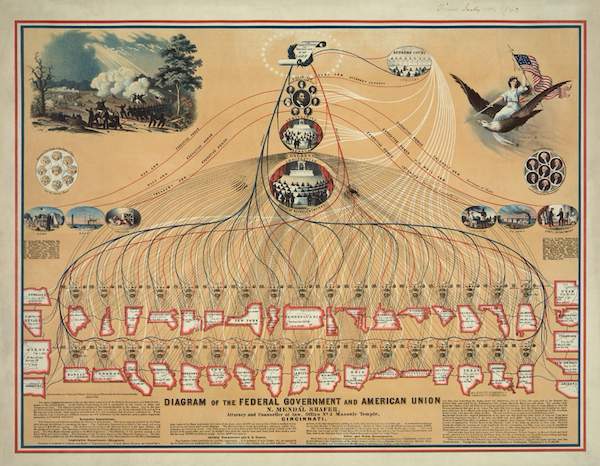

Image: Shafer via Wikimedia Commons (CC0 1.0)

No Comments