What happens when official information aimed at changing people’s behaviors clashes with popular accounts and folk theories? In a time of conspiracy theories and conflicting narratives about everything from pandemic precautions to TikTok, this question is often top of mind.

In a recent article with Laura Doering, we examine this question in the context of a financial inclusion program in Colombia. Financial inclusion, or the incorporation of low-income consumers into the formal financial sector, has become a priority for governments, banks, and international organizations around the world, and Colombia is no exception. According to the World Bank, fewer than half of Colombians have a bank account, and the poor are especially unlikely to have one.

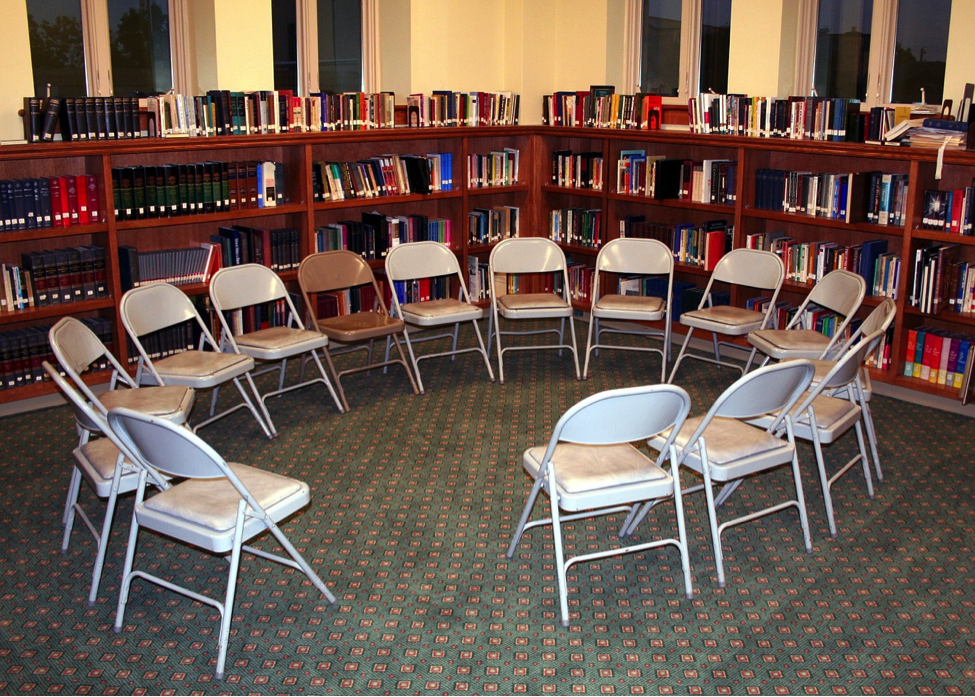

In response, the Colombian government launched a national microsavings program aimed at motivating low-income Colombians to engage with formal finance, as well as supporting them in saving money. Over the course of a year, more than 46,000 Colombians living in public housing projects across the country participated in the program, meeting every two weeks with a savings group composed of approximately 15 of their neighbors and accompanied by a program facilitator.

By some metrics, this program was a success. Participants were given access to and assistance with low-cost mobile banking accounts, they received financial education from their facilitators, and most notably, their monthly savings increased by 300% on average – all of which the literature would expect to increase formal financial engagement.

A counterintuitive outcome

However, panel survey data revealed a surprise: participants’ interest in formal financial services like bank accounts decreased between the beginning of the program and the end.

Responding to the question “Would you be interested in having a financial product (savings/credit/insurance, other) with a financial institution?” 74% of respondents said “yes” at the outset of the program. By the conclusion, that number fell to 65%, a drop significant at p < .001 and robust to controlling for the amount participants saved, demographic characteristics, and geographic factors, as well as when including individual fixed effects.

We explored several possible explanations for this finding—Was the drop in interest a result of macroeconomic shocks? Did members have unpleasant experiences at bank branches? Was the decline driven only by members who failed to save money? Did members find the groups so satisfactory that they no longer needed formal finance?—but we found that none of these could fully explain the result.

To investigate further, we drew on interviews with a total of 105 savings group participants and staff in three cities spread over the beginning, middle, and end of the program, as well as ethnographic observations of 28 savings group meetings. We used insights from microsociology and organizational sociology to theorize the process that best explains these findings.

Elaborating on the abstract

We found the answer to this puzzle in a process we term “elaborating on the abstract,” as organizational efforts to disseminate abstract information at scale merged with lively, group-based acts of meaning creation.

The government aimed to achieve its financial inclusion goal in part by providing information intended to encourage participants to engage with banks. Because of the program’s size, they condensed this information into simple, abstract formats, as large organizations are wont to do when disseminating information at scale. This compression of information into its simplest form makes it easier to transmit across people and space, but also strips it of time, place, and context. Savings group facilitators were trained in several standardized financial education modules, and instructed to deliver them to their groups at various points throughout the program.

When savings group members received this abstract information, they expanded on it to make it concrete and applicable in the context of their lives. In group discussions, they often worked collectively to elaborate on official information and come to conclusions about the nature and value of formal banking; these discussions often emphasized banks as risky institutions that charged outsized fees, depleted savers’ funds, and levied fines without warning.

Elaborating on the abstract prompted a loss of interest in the financial sector through three mechanisms. First, group members shared their personal experiences of banking with one another; these experiences were often negative, perhaps unsurprisingly given the economic marginalization of the program’s target population. Second, group members repeated second-hand stories, rumors, and fuzzy information about formal finance that muddied the waters and made it difficult to differentiate facts from potentially apocryphal accounts. Third, they “colored in” neutral, factual information by attaching a negative valence to it. For example, when describing bank account fees chipping away at their savings, several respondents described these fees as theft on the part of the bank.

This tendency to prioritize negative information that we observed in these groups is not an anomaly; research in other contexts has shown that groups and individuals tend to anchor on negative themes and overvalue the reliability and importance of negative information.

Nonetheless, there were exceptions. We found that two additional – although rare – mechanisms could counteract this tendency, creating space for more positive interpretations of banking. These were the presence of someone “playing defense” by challenging misinformation or counteracting cautionary tales in the moment, or of someone championing finance by emphasizing positive experiences and supporting group members in their interactions with new banking tools.

Broader applications

The concept that we theorize, elaborating on the abstract, articulates a process of informational compression and expansion. First, organizations reduce complex information into simple components to facilitate its widespread dissemination. Then, groups expand upon this information through elaboration, by personalizing it, contextualizing it, and making it concrete. In doing so, they can shift meanings and interpretations away from the intentions of the disseminating organization, leading to unexpected outcomes like those we observed. In the realm of economic sociology, these findings complement and extend existing theories of financial preference by highlighting the role of organizational and small group dynamics.

However, we believe this process is also applicable to other contexts in which official information is shared and then circulated, such as public health interventions. We theorized this in the case of resistance to vaccines, a phenomenon that persists despite overwhelming evidence of their health benefits. Large organizations like the CDC disseminate simplified information about vaccines to a large, diverse audience; parents may then engage with one another to interpret and elaborate on this information. While our empirical case involved co-located groups, online forums could serve a similar function, potentially amplifying the negative tenor of discussions and the speed at which anecdotes and fuzzy information spread; indeed, online discussions may swing negative even more readily. This process may well be applicable to current messaging around COVID-19, which likewise has broad universal guidelines that people receive from official sources and then interpret and implement in their own lives. The current context has the added complications of public health messages changing as knowledge about the virus advances, and official narratives from different sources contradicting one another. These complications may render the collective process of elaborating on the abstract through in-person or virtual discussions with others even more influential – and potentially generative for further explorations of this process.

Read More

Doering, Laura and Kristen McNeill. “Elaborating on the abstract: Group meaning-making in a Colombian microsavings program” in American Sociological Review 2020.

Image: justcallmeang via Pixabay

No Comments