Social science historians have long recognized that war was the rule rather than the exception in early modern Europe. The so-called “Second One Hundred Years’ War”, for example, pitted France and Britain against each other in at least six major confrontations between 1688 and 1815.

The motivations behind these armed conflicts were manifold: religious rifts, dynastic interests, territorial expansion, and commercial rivalry.

But these wars had political implications that are felt to this day. Following Charles Tilly’s dictum, state-making was inseparable from war-making during this period. Armies and navies were costly. To pay for their services, taxes had to be raised.

The rulers of the nascent nation-states thus had every incentive to set up an administrative infrastructure for effective taxation.

Beyond politics, war also went hand in hand with early capitalist development. Not only did rival economic interests motivate armed conflict, the early modern wars also opened new business opportunities, especially in seaborne enterprise. More often than not, these opportunities entailed high-risk, high-return undertakings such as slave trading or illicit interloping trade.

In my new book, I consider a particularly curious one among these war-related opportunities: privateering enterprise.

Its central aim was to erode the enemy’s flow of returns from trade. When war broke out, rulers commissioned private ship-owning traders to fit out vessels as corsairs to raid enemy shipping. Captured vessels and their precious cargo were then auctioned off as prizes, usually, but not always at the corsair’s home port.

Privateering thus was a genuine economic form of warfare.

The historical roots of privateering are complex, and, too often, it is confused with piracy. The illicit pursuits of pirates did not distinguish between ally, neutral and foe. Pirates operated entirely on their own accord and outside of local laws.

Corsairs, or privateers, in contrast, were legally sanctioned by their own sovereign. They received a written commission—a letter of marque—that licensed them to attack enemy merchant ships. This authorization was valid only during times of war, and it extended exclusively to the capture of enemy vessels, whereas the rights of neutral ships were to be respected.

Strict regulations, the requirement to pay bonds of surety, and the threat of severe punishment for transgressions into piracy ensured that privateers stayed within the boundaries of the law.

The case of Saint-Malo

In the book, I show how important the role of privateering was for the economic growth and the social cohesion of the merchant community of Saint-Malo. Perched on a rocky islet off the coast of Brittany, Saint-Malo was a pivotal port in the French Atlantic economy since the late seventeenth century and up to the French Revolution.

Beyond the returns from privateering, Saint-Malo’s merchant elite grew rich from their engagement in the colonial trade with Spanish America. They extended their business interests into the South Sea. They also secured privileged access to markets in India and China, and they pioneered the coffee trade with the Arabian Peninsula.

To seize these promising opportunities, the traders of Saint-Malo formed venture partnerships. Their partnerships allowed them to pool capital and material resources and to spread the risks that were inevitable with such undertakings.

Fortunately, a vast and rich depository of partnership contracts from Saint-Malo has been preserved. The contracts document in great detail who the partners were, where they came from, and how large their shares in the enterprises were.

The sources also tell us what kind of venture the business partners engaged in, the type and size of the ship they employed, and whom they hired as their captain.

Once coded into a relational database, these qualitative archival sources lend themselves to a quantitative network analysis.

My findings reveal that the partnerships that the merchant elites formed in their privateering ventures gave rise to a cohesive community network. Privateering enterprise was essential in this historical place because it enabled the local merchant community to secure its hold on established trades, seize new opportunities, and withstand the threats of armed conflict.

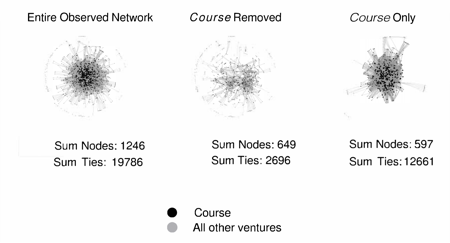

For one exemplary period (1698-1720), the following graph illustrates to what extent privateering partnerships served as an organizational linchpin that held together the entire merchant network—similar to a broker who builds bridges between otherwise separate clusters.

The left-hand graph shows the complete observed network of partnership ties. It offers a bird’s-eye view of a well-embedded, close-knit community. The nodes represent individual merchants.

Using simulations, the center graph shows how visibly sparser and fragmented the network becomes if privateering ventures were absent. The important insight is, however, that the removal of other ventures does not result in the same dramatic decrease in cohesion.

The right-hand graph illustrates how densely linked the privateering ventures remain if we detach and isolate them from the complete network. Taken together, these graphs provide illustrative evidence that privateering ventures did indeed play a central integrative role in the merchant community.

The story does not end here. It turns out that privateering supported cohesion because it served as an ideal launching pad for the careers of rookies in seaborne enterprise. Few barriers to entry existed and the costs of floating a privateering venture were not prohibitive.

For many, privateering was the entry ticket into the world of international commerce. As the careers of these merchants unfolded over time, they eventually branched out from privateering into other trades.

When their initial privateering ventures were successful, these budding maritime entrepreneurs routinely reinvested the returns and moved on to their next venture. Seeking partners for the new venture, they relied on trusted peers from earlier enterprises as much as they recruited fresh investors.

At the same time, a merchant’s erstwhile partners may well have collaborated in still other enterprises of their own: “a friend of a friend is a friend” translated into “a former business partner of my current business partner is likely to be someone I would do business with in the future.” Bonds between a trader’s old and new business partners were forged in this manner.

Cohesion among the merchant elite of Saint-Malo emerged from this enchainment of past and present partnerships over the course of careers that typically began with privateering.

Ultimately, understanding how privateering enabled these career trajectories and networks also deepens our understanding of the local organizational foundations of early capitalist development.

Read more

Henning Hillmann. The Corsairs of Saint-Malo: Network Organization of a Merchant Elite Under the Ancien Régime. Columbia University Press (The Middle Range Series), 2021.

Image: Bibliothèque Nationale de France (used with permission)

No Comments