Strikes at Kaiser Permanente, John Deere, and Kellogg’s have brought renewed attention to workers’ clout when they organize unions. Collective bargaining agreements can convert wage gains from a temporarily tight labor market into durable gains for workers. As a result, U.S. employers often pull out all the stops to defeat new union organizing drives. Many employers bet that it’s better to break the law and keep workers from getting a union than to be stuck with collective bargaining for years to come.

Historically, one powerful way that employers have kept unions out is by avoiding hiring union supporters in the first place. If an employer can systematically weed out applications from “bad apples” and pro-union malcontents, then the risk of a successful future organizing drive is mitigated. For example, a case study of hiring in a 1990s foreign auto plant found that managers avoided workers with prior auto experience, because that meant prior employment at the unionized Big Three American automakers. No auto experience, no union problem.

Given this prior evidence on employers’ vehement opposition to unions, we were curious about whether employers still discriminate against union activists who apply for jobs. On the one hand, employers seem highly motivated to fight new union organizing drives. On the other hand, these drives are so rare, as union membership has fallen steadily for decades, that employers might be focused on other priorities in the hiring process.

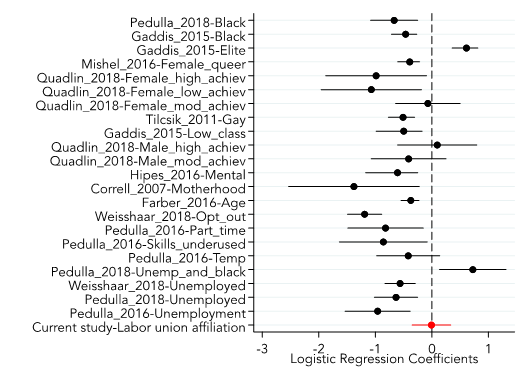

Our new study does not find evidence that employers discriminate against union supporter job applicants. Using a correspondence audit study, we find that employers were equally likely to call back hypothetical union-affiliated applicants as they were comparable applicants without union affiliation for entry-level, frontline jobs in Chicago.

Union Discrimination at the Hiring Stage

Union representation has been on a long decline, in part spurred by employer aggression against organizing. In the 1980s, employers stiffened resistance to organizing drives, arranged replacement workers during strikes, and fired pro-union troublemakers. But much anti-union employer action seems to be in reaction to relatively rare events in which union threat and power becomes salient and urgent (like the recent Kaiser Permanente and Kellogg’s strikes). Do employers also engage in anti-union discrimination before organizing begins?

We tried to answer this question with a résumé correspondence audit study at the initial point of hire. We submitted hypothetical résumés of two applicants—one with union affiliation and one without—to test whether employers in one labor market with a sordid history of unionization—Chicago—screened out union supporters before they could even strike. We used a correspondence audit method because it allows us to match the applicants on every other characteristic that might matter in hiring, such as educational attainment (both had high school degrees) or work experience (both had several previous jobs in entry-level jobs in Chicago). In so doing, the correspondence audit method isolates employers’ reaction to an applicant’s union affiliation and support, net of work experience, education, or other confounders.

Once we made the résumés, we submitted 1,025 of them, and corresponding cover letters, to 514 entry-level, high school graduate jobs in Chicago. We conducted the study from October 2019 to October 2020, spanning an eventful period of a Chicago teachers strike, seasonal fluctuations in hiring, COVID shutdowns, and the initial recovery.

To measure employer responses to union-affiliated applicants, we compared the callback rates between applications with and without disclosure of labor union affiliation from a prior job. We found that employers were no less likely to call back union supporter applicants than applicants with no union affiliation. This does not necessarily mean that employer discrimination against union-affiliated applicants has ended. But it does suggest that, at least in the frontline Chicago labor market, union affiliation did not significantly decrease entry-level applicants’ chances of landing a callback for a job.

One concern in many audit studies is whether the employers being audited understand the signal researchers include on a resume. In studies of racial discrimination, this has led to debates about race, class, and the meanings of racially coded first names that are typically used to signal race. In our case, we wanted to know whether prior union affiliation was actually understood by employers. While we could not ask the specific employers in our study, without tipping them off to the nature of the experiment, we did conduct an online survey asking respondents to rate the application materials we used. We were reassured that 80 percent of respondents thought that our union affiliation application materials came from a union supporter.

Explaining The Effects of Union Affiliation on Hiring

To understand this result, surprising in the context of prior consensus about employers’ widespread anti-union discrimination, we interviewed 20 Chicago employers. These conversations suggested that labor unions are typically not a focus of employers of non-college workers, at least during the hiring stage.

Managers, employers, and human resources managers we spoke with insisted that information about labor union participation would not impact hiring. This was mainly due to the very low likelihood of workers unionizing to begin with. One small café and meat market owner, for example, said that he only has a few people working for him and he has grown to know them personally. One human resources manager of a large manufacturing establishment expressed the sentiment that “unions are dying, slowly and surely. It’s really a matter of time.”

Our results suggest that employers may not be weeding union supporters out at the hiring stage. But the large strikes this month illustrate the potential power of union organizing for workers. Perhaps if the salience of union threat increases, future studies will find employers returning to blacklist techniques.

Read more

A. Nicole Kreisberg and Nathan Wilmers. “Black List or Short List: Do Employers Discriminate Against Union Supporter Job Applicants?” in Industrial and Labor Relations Review 2021.

No Comments