Corporate managers used to track stores through weekly or monthly sales records, phone calls, and in-person visits. Today, software creates near-constant – but not necessarily meaningful – communication between store managers and their senior corporate counterparts.

Metrics like “sales per hour,” which captures a store’s sales revenue per labor-hour, now drive moment-to-moment corporate decisions about staffing. These just-in-time scheduling practices try to match the sales volume to workers on the clock at any moment.

The goal is to minimize labor costs. Yet, the result may not be higher profits.

Our recent book finds corporate’s use of remote technology to determine personnel needs leads to bad management decisions and undercuts the autonomy of store-level managers. Corporate attempts to wield control over daily operations are decontextualized from what’s happening in the stores. These practices cause unintended consequences like dissatisfied customers, declining sales, and disgruntled workers.

For example, corporate counts “footfalls” of people entering and exiting the store. If children run in and out of a store as they play, footfalls increase but purchases do not, counting against worker productivity. Metrics often capture an inaccurate sense of worker productivity yet are reified as “objective data” that drive corporate decision-making.

Thus, we conceptualize this labor process as a service quadrangle. Building on theories of the service triangle, an arrangement composed of managers, workers, and customers, the service quadrangle treats corporate- and store-level managers as distinct groups.

We theorize the dynamic relationships between workers, customers, corporate managers, and store managers, given the growth of corporate surveillance technology. Alliances form, conflicts surface, and allegiances shift depending on the situation and the workplace composition.

What a Mess!

Take a messy clothing store for example. “People will literally just pick up a shirt, look at it, and then just toss it,” explained someone who had worked at Forever 21. “That’s how … the store gets so, so messy.”

Yet corporate management no longer factors the mess into its calculation of the ideal sales-to-labor ratio. Store managers often lack the authority to override these decisions. With understaffed stores, workers can’t keep the store tidy and respond quickly to customer requests.

Store managers told us about how frustrating it was to watch corporate run their shops into the ground by relying on their interpretation of metrics.

One store manager noted how corporate management used to criticize stores

with a high sales-per-hour ratio, since “that would mean that your store doesn’t look that good. . . . You’re not helping customers enough.” But since they’ve shifted to focus on short-term rather than long-term sales goals, corporate is “championing you on the conference call, they’re like, ‘Great job!’ [But] the store must look awful if you have such a difference between hours and sales.”

Irritability among shoppers becomes similarly palpable, since the products are harder to find and the fitting rooms are overflowing with unwanted items abandoned by previous occupants. Many simply leave and shop elsewhere.

Worker-customer relations also deteriorate when the store is too understaffed to keep clean. The constant need to refold sweaters and buy-one-get-one-half-off jeans tests workers’ patience when too few workers are on the clock.

Shoppers also look down on workers, especially in messy stores. One boutique worker said she’s seen as “a garbage lady.”

Other workers don’t feel seen at all. As another former employee of Forever 21, explained: “people won’t even really look you in the eye.”

Labor practices that lead to “the mess” undermine alliances between customers and workers. They also drive customers out of brick-and-mortar stores, who become willing to trade trying on clothing in messy stores for guessing about fit on orderly websites.

As the mess demonstrates, relying on simplistic metrics reported through remote technology has divided corporate and frontline managers, frustrated workers and consumers, and helped hasten declining sales.

Surveillance on the Shop Floor

Surveillance stretches across each point of the quadrangle, from corporate manager uses of “secret shoppers” and customer surveys to worker self-regulation and store manager corrections of how cashiers deliver the corporate-concocted sales script.

Watchfulness has several aims. One is deterring theft. Workers are asked to closely monitor customers to prevent shoplifting.

Anti-Black racism manifests in these practices, with many store managers and workers racially profiling Black people.

Store managers even direct Black employees to follow Black shoppers around the store. One Black worker recounted how regularly she was asked to follow Black men in her store, noting, “That’s one of the reasons why I don’t really like working there because I didn’t really like that.”

Store managers also search workers’ belongings before they depart for the day. A different Black worker described that despite being expected to wear store merchandise, she was accused of stealing a sweater she had bought and for which she had a receipt.

She said managers “did try to apologize to me afterward, but there’s very little that you could say to someone after you’ve accused them of something like that. . . . I’ve had people try to follow me and stuff like that but then to have my own manager accuse me of something like that—like that’s just really insulting.”

Racist surveillance patterns trouble Black workers and motivate many to quit.

Routinization & Resistance

Another corporate goal of surveillance is routinization. Corporate managers direct their store-level counterparts to train and monitor sales workers to ensure they use the prescribed scripts.

Abercrombie & Fitch workers, for instance, had to say “what’s up” as shoppers arrived and “catch you later” as they departed. Such taglines give workers no wiggle room, leading one former worker to describe feeling “more robotic.”

Others highlighted how scripted greeting prevented interacting with customers in socially appropriate ways, like saying “what’s up” to an elderly shopper. Store managers constantly surveil workers’ use of scripts. “Sometimes the [store] managers hide behind . . . indoor plants in there,” remembered a former Abercrombie Kids worker.

Corporate also sends “secret shoppers” or people who act like customers but are actually assessing how well the staff meet company requirements. Secret shoppers mean that store managers and their workers could be under in-person corporate scrutiny at any time.

All of these exacting corporate practices foment resistance among workers. Many refused to consistently utter the scripted greetings or “upsell” customers. Persuading shoppers to buy extra stuff, especially store-sponsored debt, can be an uncomfortable enterprise.

That’s why some workers opt out, even though corporate metrics will inevitably detect and chastise low performers.

Store credit card sales offer a case in point. One former worker refused to push them, saying “credit cards are the worst thing ever.” Her record was shared via “a board with the percentage everyone had each month” in the break room. “I was always at the bottom,” she recalled. The display irked her but deepened her disdain rather than inspiring compliance.

Surveillance remains constant in retail clothing, as does workers’ navigation of power-laden dynamics within the service quadrangle.

Read more

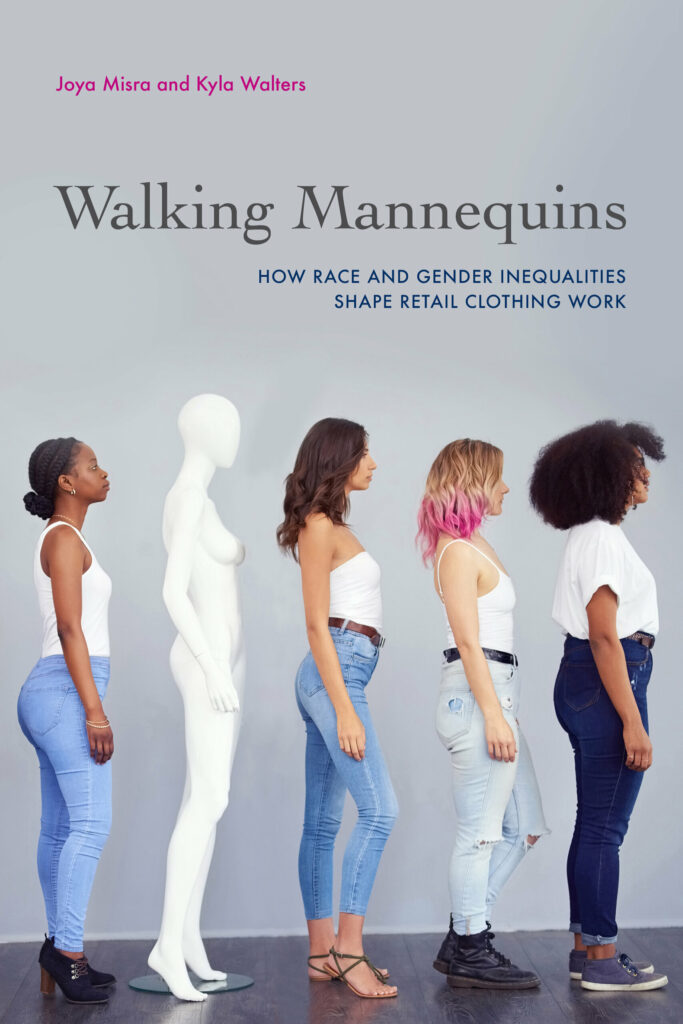

Joya Misra and Kyla Walters. Walking Mannequins: How Race and Gender Inequalities Shape Retail Clothing Work. University of California Press 2022.

No Comments