Surveillance is everywhere these days, but its punitive impacts are experienced unevenly. Police patrol minoritized communities, algorithms discriminate against people of color, borders screen out migrants and refugees, and identification systems mislabel gender nonconforming individuals.

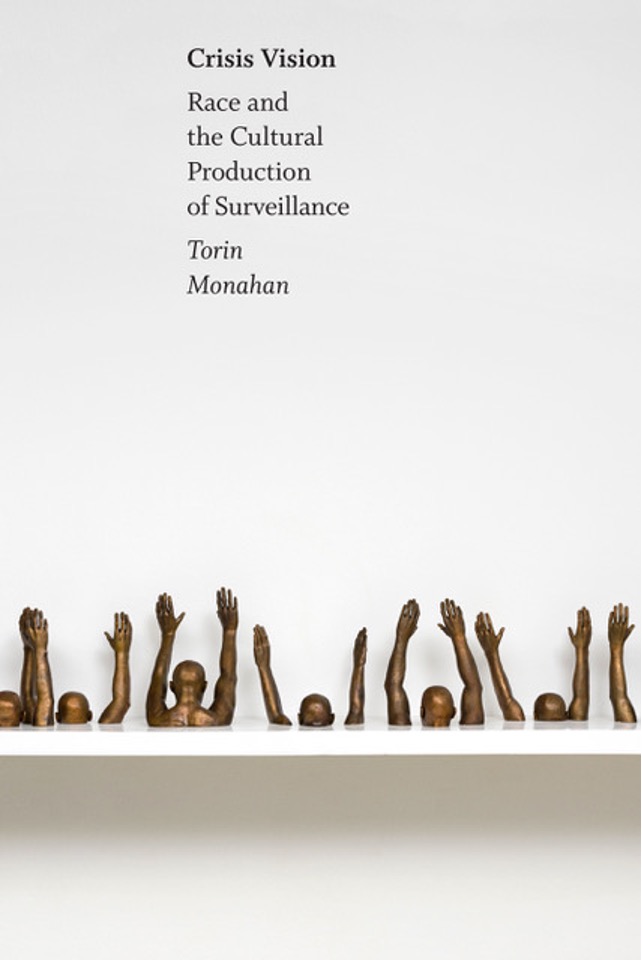

Growing concern over surveillance has spawned many colorful forms of resistance. In my recent book, Crisis Vision: Race and the Cultural Production of Surveillance, I analyze dozens of resistance artworks that seek to interrupt surveillance abuses.

By paying attention to the work of artists, I argue that we can learn about the deeper logics of surveillance and become more reflexive about our responses.

Resistance frames

Resistance artworks approach surveillance in differing ways. I divide these artistic approaches into five resistance frames.

The first is “avoidance,” which provides resources for people to escape surveillance as individuals on a case-by-case basis. This can take flamboyant forms, as with face-makeup designs for evading facial recognition systems, but it could also include things like ad-blockers or other privacy-enhancing tools.

The frame of “transparency” sheds light on state and corporate surveillance practices that aim to make populations legible. Artworks in this vein do things like critique U.S. counterterrorism programs that targeted Muslim-American communities during the War on Terror.

A different artistic tack is to call out how people might unwittingly participate in surveillance programs and bear responsibility for them. This frame of “complicity” includes projects on the collateral damage of U.S. drone strikes, on one side, and abstract big-data systems that manipulate people without their awareness, on the other.

The fourth frame, “violence,” shows how surveillance amplifies existing prejudices. The artworks in this category focus on structural violence, such as global refugee crises, and symbolic violence, such as public shaming through the online distribution of police mugshots.

The book wraps up with the final frame of “disruption,” which foregrounds the racializing effects of surveillance and charts avenues for collective survival. Artworks of the Black Lives Matter movement, confrontational museum installations on police shootings, and dance performances on the afterlives of slavery each strive to disrupt the dehumanizing effects of surveillance.

Problem spaces

Resistance art tackles power imbalances in society. It helps viewers gain perspective on today’s social problems and their role within them.

For instance, James Coupe’s Watchtower installation features a massive wooden watchtower with video screens of people performing piecemeal tasks through Amazon’s “Mechanical Turk” crowdworking platform. Artworks like this one draw attention to the ways that digital platforms pull people into exploitative labor relations and aggravate their economic precarity.

Dread Scott’s installation Stop offers a different example. It exposes museumgoers to video recordings of men of color relating how many times they’ve been stopped by the police. This artwork compels viewers to confront the reality of Black and Brown people being targets of routine police surveillance and violence.

These and other artworks do more than represent problematic situations—they also implicate viewers in those situations. By using Amazon services or living in a policed society, we contribute to everyday surveillance that benefits some at the expense of others. Responsibility rests not only on institutional actors but on society as a whole.

Collective constraints

Although my focus is on artworks, the artistic frames covered in the book could just as easily apply to academics or activists as they do to artists. Together, they reveal some of our collective constraints in dealing with the problems of racializing surveillance.

Namely, there is a tendency to presume universal exposure to surveillance and to stress individual solutions to it. This makes it difficult to recognize the discriminatory applications and outcomes of surveillance programs.

Additionally, when people appeal to the law or advocate for the protection of human rights, these discursive moves often ignore the ways that such legal orders are predicated on the exclusion of racialized bodies.

Learning from artists, we might find value in maintaining discomfort and tension, of sitting with such contradictions and recognizing their generative potential. Cultural change may even emerge from places of uneasiness and uncertainty.

The most productive interventions, in my reading of these artworks, are those that emphasize opacity over visibility, collective coexistence over violent division.

Conclusion

Surveillance is more than just watching. It is an exercise of power and a tool of domination.

Taking a critical look at artistic forms of resistance to surveillance can reveal these deeper logics. It can also draw attention to the limitations of popular approaches to addressing social inequality and vulnerability.

Reformist impulses, which may seem entirely pragmatic and rational, may do little to correct larger surveillance problems if they fail to grapple with the inherent exclusions at the heart of the liberal project.

Read More

Torin Monahan. Crisis Vision: Race and the Cultural Production of Surveillance. Duke University Press 2022. The book’s Introduction is available here.

No Comments