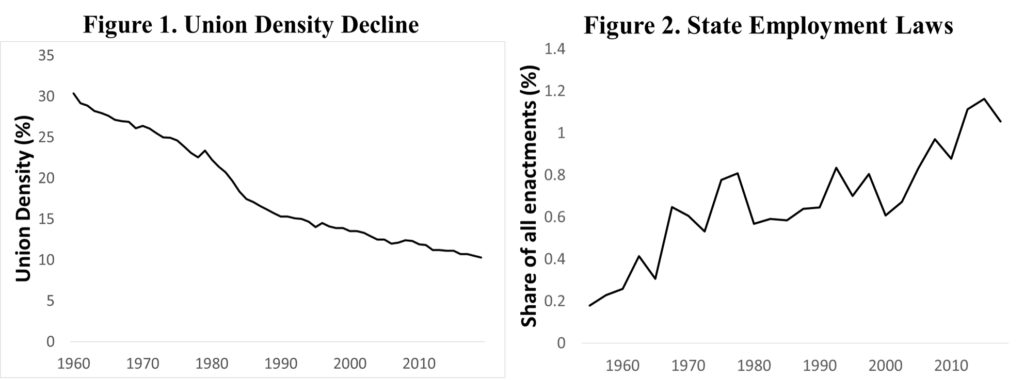

At the same time that union density in the United States has declined and labor law has withered, employment law has flourished, proliferating at the subnational level and expanding into new substantive domains (see Figures 1 and 2 below).

As a result, for the vast majority of 21st century workers, what rights and protections remain come not from labor law and the mechanism of collective bargaining, but from employment laws and the mechanisms of regulation and litigation.

When it comes to protecting workers’ rights, employment laws are clearly inferior to labor law. They are often under-enforced, under-utilized, and circumvented by forced arbitration. In contrast to labor law, they lack built-in mechanisms for expressing voice and generating collective action in the workplace, tending instead to further atomize workers. But in most cases of workplace exploitation, workers have little other recourse than to turn to employment laws—they’re all they have left.

How did this institutional shift in workplace governance occur?

Some scholars have suggested a link between the decline of labor unions and the rise of employment law. Theodore St. Antoine, for example, posits that “part of the growth we have seen in employment law, as distinguished from labor law, is attributable to the decline of organized labor. Government has had to step in to fill the vacuum.”

The notion that state legislatures turned to employment laws to protect an increasingly non-unionized, vulnerable workforce has a certain intuitive appeal. But the role of organized labor remains unclear. Did labor unions sit idly by while state legislatures built new workers’ rights? Or did unions, even as they declined, push for greater protections and rights for all workers? Or did the growth of employment law actually contribute to the decline of unions, as some economists have suggested?

We know that labor unions have historically been strong advocates for universal social welfare programs and redistributive policies—but their interest in vigorous state regulation of the workplace is less clear. From Gompersian voluntarism to the “government substitution hypothesis,” there has long been a question of whether state intervention helps or hurts unions—in particular, whether protective labor laws might undermine workers’ incentive to unionize by providing for free what workers might otherwise get through their unions.

There isn’t a lot of empirical evidence to support this idea: as Richard Freeman has shown, there’s actually more evidence that causality works in the reverse direction, such that “more highly unionized states are…more likely to pass protective legislation.”

The problem is that we still do not know in which way the causal arrows point. It could be that states that are more likely to enact stronger employment laws are also more likely to have stronger unions, and there’s little direct relationship between the two.

In a recent paper, I try to dig a little deeper to flesh out the nature of the relationship, using an integrated multi-method approach to move us incrementally closer toward drawing causal inferences with greater confidence. The goal is not to resolve the causal inference puzzle definitively, but to make piecemeal progress toward clarifying causal relationships and building theory.

Although the resulting inferences are circumspect by design, the implications of the findings reach more broadly, to normative and empirical questions as old as the American labor movement itself. Does protective labor legislation complement or substitute for unionization? How compatible is trade unionism with political engagement? When and how do unions transcend the interests of their members and advocate for all working people? In contemporary debates over how to best secure workers’ rights and redress power imbalances in the workplace, these remain pressing questions.

My statistical analyses confirm that states with higher rates of union density do boast more robust employment law regimes: they maintain higher standards for work conditions and offer workers a wider range of substantive rights and protections. And while unionism predicts employment law enactments, employment laws do not appear to cause or accelerate union decline: All else equal, the higher the rate of union density and the less decline over time, the greater the state’s propensity to enact employment laws.

The models point to Pennsylvania and Maine as good “deviant” (outlier) cases for further examination at close range: Pennsylvania had many fewer major employment laws than the model would predict, given its high level of union density and other relevant factors, and Maine had many more employment laws than predicted, given its merely average rate of union density.

My case studies of these states turned up voluminous evidence that unions did indeed play an integral role in efforts to enact stronger subnational employment laws. Even when bills failed to pass or were ultimately watered down, organized labor was consistently on the front lines, pushing for stronger protections for workers. (Except in policy campaigns to expand LGBTQ rights in Pennsylvania, where organized labor was nowhere to be found—a reminder of unions’ mixed history on issues of diversity and inclusion.)

This analysis does not provide dispositive empirical evidence of a causal relationship or refute the notion that the relationship may yet be spurious in other cases. But the evidence assembled is difficult to square with alternative causal arguments and it lends concrete support to the hypothesized causal pathway connecting labor unions to employment laws. Although unions did not build these employment laws alone—multiple forces clearly played a role in each case—unions ought to be considered significant “contributing causes” of their growth.

Even as union membership continued its seemingly inexorable decline and the myriad positive “spillover” and “threat effects” of unionism vanished—along with their once-buoyant effects on the moral economy, as Bruce Western and Jake Rosenfeld have shown—unions were hard at work enacting many of the subnational employment laws that continue to structure and regulate the employment relationship today.

Unions were motivated to fight for stronger employment laws for a variety of nonexclusive reasons, including their apparent commitment to advocate for all working people, not just union members. In most of the policy campaigns I examined, unions publicly trumpeted their role as guardians of all workers’ well-being. Future research should explore whether this public stance, and their ability to achieve policy victories, have been advantageous for unions, resulting in increased membership or more favorable views of unionism generally. This is a question that has loomed over the Fight for $15 (“and a union”): When, whether, and how do employment law campaigns complement unionization?

The contribution of this analysis is that it allows us to more confidently point the causal arrows in the right direction and move on to the next stage of analysis. We can now dig deeper into the role unions have played, and continue to play, in building the primary sources of workers’ rights and protections in the 21st century. And we can state with greater confidence that the new federalism in work regulation constitutes one of organized labor’s most significant and enduring legacies.

Read more

Daniel J. Galvin. “Labor’s Legacy: The Construction of Subnational Work Regulation” in ILR Review 2020. For a free, pre-publication version of the article, click here.

Daniel J. Galvin. “From Labor Law to Employment Law: The Changing Politics of Workers’ Rights” in Studies in American Political Development 2019.

Image: Nick Youngson via Picpedia (CC BY-SA 3.0)

No Comments