The debate about the impact of automation on the labour market has been ongoing for several years, as new technologies are taking over jobs currently performed by workers. Our study discusses how workers are responding to the growing automation of production processes, and why human capital adjustments are crucial for the workforce to remain competitive in the labour market also in future.

Industrial robots

Industrial robots are among the leading automation technologies of the last decades. The International Federation of Robotics (IFR) defines them as “automatically controlled, reprogrammable, multipurpose manipulators, programmable in three or more axes”, and estimates that the global stock of robots has increased from 500 thousand to almost three million units between the early 1990s and the late 2010s.

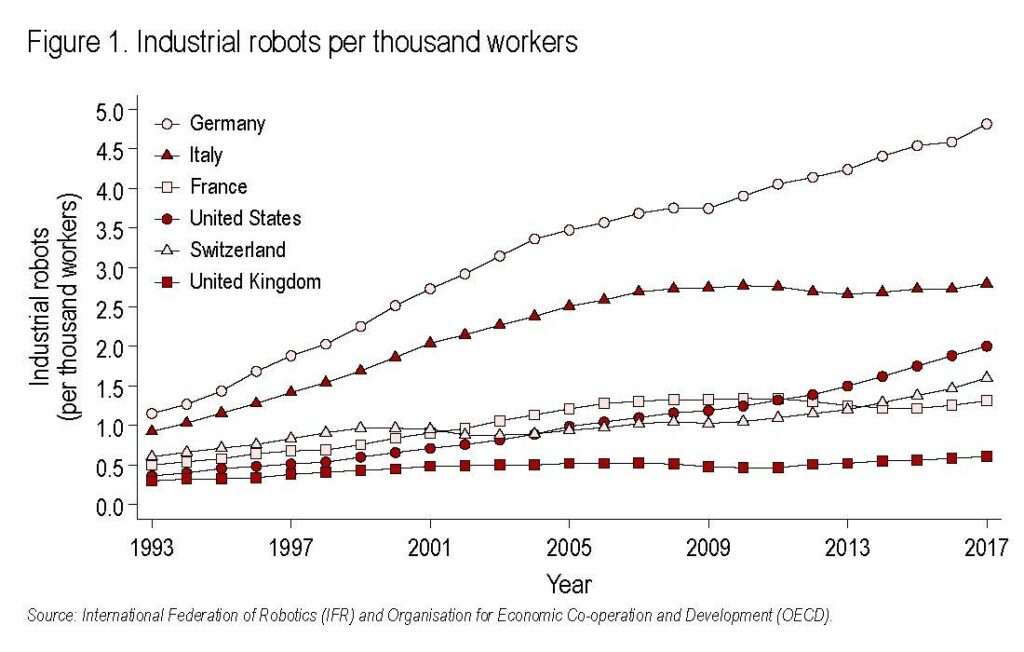

So far, robots have been mainly used in the manufacturing sector, as they can be programmed to autonomously perform manual activities (including assembling, material handling, packaging and welding). However, they are increasingly adopted also in other industries, such as the service sector. South Korea and Japan count as the major adopting countries with 10 and 5 robots in place per thousand workers, followed by European countries, in particular Germany and Italy, and the United States (Figure 1).

Robots and the labour market

From a theoretical perspective, the use of automation technologies has an ambiguous impact on labour market outcomes. On the one hand, robots may have a displacement effect—robots replace human workers in a variety of manual tasks, and therefore reduce employment and wages. On the other hand, they may a productivity effect—robots raise the productivity of adopting firms, contributing to the creation of new jobs and activities, and increasing the demand for labour.

Empirical studies have addressed the question of which of these two effects dominates in practical applications and found mixed results across countries. The introduction of industrial robots in the United States between 1993 and 2007 decreased aggregate employment by half a million workers, suggesting that these machines destroyed more jobs than they created. This result, however, does not hold among European countries, where robots have displaced low-skill workers in the manufacturing sector but have also increased the demand for labour in the service sector, leaving aggregate employment almost unchanged.

The role of human capital

When analysing the implications of automation on employment, it is important to emphasize two facts. First, not all workers are exposed to the risk of automation to the same extent. Less educated workers are more likely to be displaced, since they are often employed in manual and routine task-intensive occupations that can be performed (at least partially) by a robot.

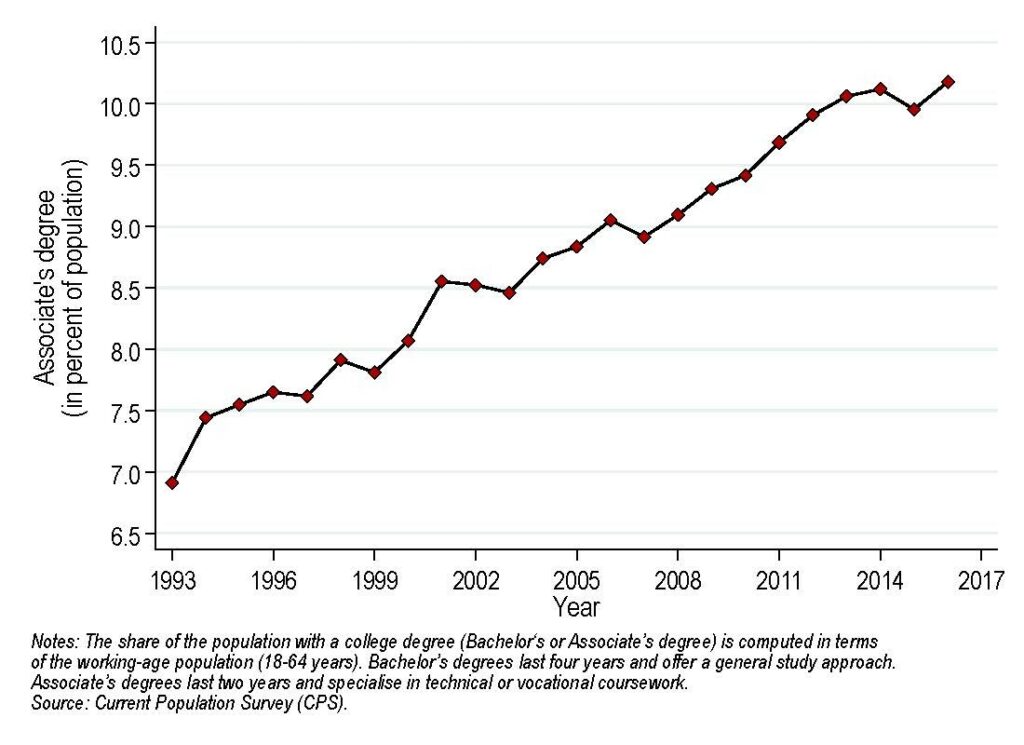

Second, jobs and activities that have been created through technological progress frequently require the interaction between humans and machines, and they cannot be performed by displaced low-skill workers due to a lack of the necessary skills. These skills could be acquired through the investment in additional human capital in form of a college degree, as college graduates are often employed in jobs that require cognitive and social skills which are more difficult to automate.

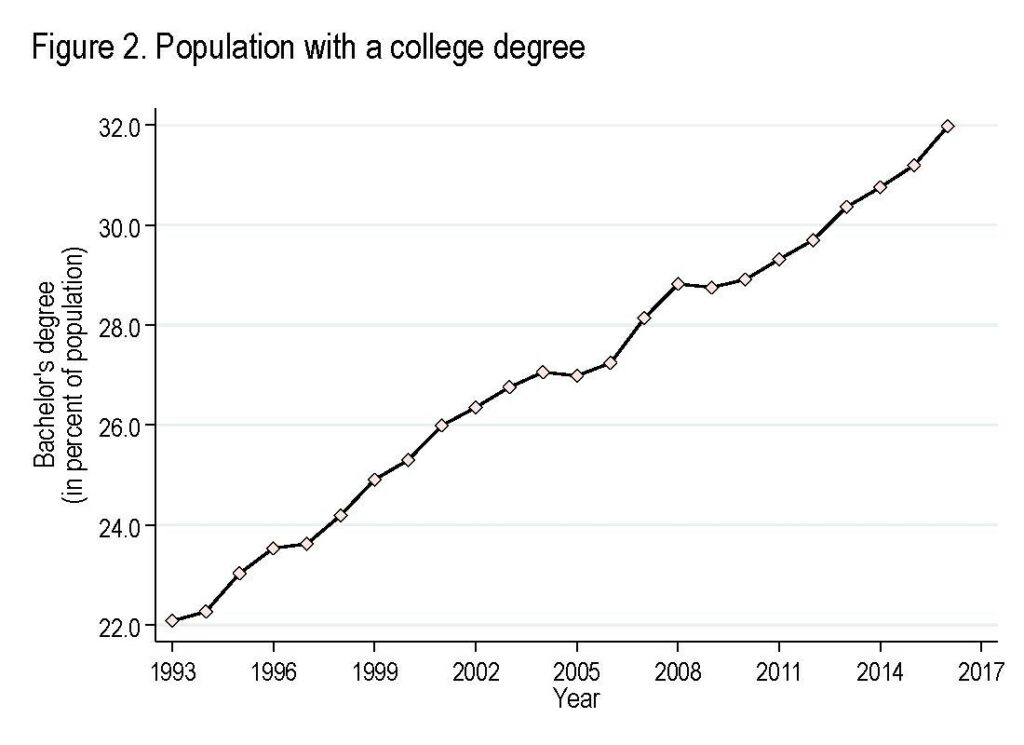

These findings raise the question of whether advances in automation technologies have contributed to the rising trend in the population with a college degree that is visible in many countries.

Human capital adjustments: A study

In our study, we address this question by investigating the effect of firms’ adoption of industrial robots on human capital adjustments of individuals across US local labour markets. We focus on the United States, as its labour markets experienced a significant contraction of employment due to the introduction of robots since the 1990s, while the share of the population with a tertiary education has increased by 50 percent (Figure 2). The analysis is conducted at the local labour market level, using commuting zones. These are territorial units which correspond to aggregations of adjacent counties characterized by large commuting flows within (but not across) them.

According to our estimates, on average, one additional robot increases college enrolment by about 5 students. In other words, for every three workers that have been displaced by robots, one individual enrols in college. These students are usually aged between 18 and 35 years and they enrol in community colleges to earn an Associate’s degree with a specialization in applied fields that are complementary to new technologies (including engineering, computer science, but also business and economics). This result suggests that the introduction of 120 thousand new robots in the US economy between 1993 and 2007 has contributed to the increase of the college-educated population by roughly 8.5 percent.

But what drives individuals to adjust their human capital to technological progress?

The short answer is that the acquisition of a college degree grants workers access to jobs that are less susceptible to automation. However, there is more, as we find that robot adoption is also increasing wage differentials between college and less educated workers. This is happening because the use of robots induces firms to increase the demand for highly skilled workers who are complementary to new technologies (productivity effect), and it reduces the demand for less educated workers who can easily be substituted by a robot (displacement effect).

In line with this finding, even young individuals who are not directly affected by automation on the workplace yet, but who observe the rising wage gap, decide to enrol in college to invest in additional human capital and benefit from higher relative wages.

Concluding remarks

The adoption of automation technologies is shaping the future of labour markets. Nevertheless, this condition should not fuel concerns about structural technological unemployment in the coming decades, since the introduction of new technologies is also boosting the demand for human labour in new occupations. With about 30 million vacant positions across OECD countries, the demand for labour is higher than ever.

Workers may, however, need to adapt their skill set in order to perform these jobs, a process that according to our results has already begun. Moreover, policymakers should facilitate the transition towards future labour markets through investments in skill-specific training programs for the “new” labour force and in retraining the “old” one. The world of work is changing, but this does not mean that we lost our race against the machines.

Read more

Giuseppe Di Giacomo and Benjamin Lerch. “Automation and Human Capital Adjustment: The Effect of Robots on College Enrolment”, available at Social Science Research Network (SSRN).

image: Ars Electronica via flickr (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

This post is adapted from the authors’ article on LSE Business Review.

No Comments