Interracial solidarity – the willingness of white workers to unite with racialized others, especially Black people, against capital – is a question that has haunted the institutionalized U.S. labor movement from its birth in the 1860s to the present day. We need only look to the white working class voters who support Donald Trump for just one example of this persistent challenge.

Unfortunately, the existing research is ill-equipped to explain the conditions that enable and constrain interracial labor solidarity. The relevant scholarly debate turns on an either/or question: did organized labor in the United States exclude or protect Black labor? On one side, scholars emphasize unions’ racially exclusionary practices. On the other side, scholars have focused on how some unions were largely inclusive. As readers, we are meant to make three inferences. First, while conservative whites were certainly racist, progressive whites recognized Black workers as their equals. Second, U.S. labor history’s protagonists were whites, while Black people were the passive beneficiaries or victims of white workers. Third, white progressives’ class analysis of capitalism was correct: employers do use racism to divide and weaken the working class.

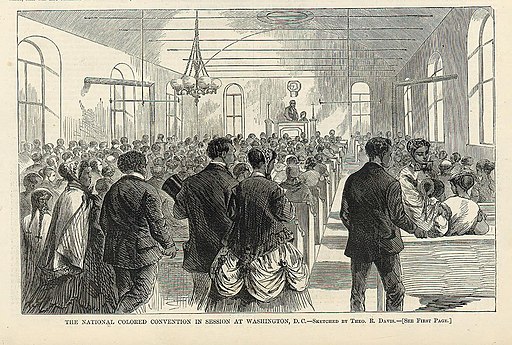

Both approaches, however, are silent on the ways in which domination under slavery continued to structure the lives of Black people after the Civil War. To address this gap, we ask the following question: Given the fact that labor leaders in the years following the U.S. Civil War professed to be abolitionists, why did the cause of interracial solidarity fail to gain traction in postbellum organized labor?

Our answer, which we advance in a new study, is that neither progressive nor conservative white trade unionists reckoned with the unfinished project of Black emancipation: what Saidiya Hartman calls the “nonevent of emancipation” and the “afterlife of slavery.”

The existing scholarship touts examples of racial inclusion that are in fact scenes of Black subjection. In the internal politics of postbellum organized labor, white trade unionists pushed a vision of emancipation that privileged white labor’s liberation from industrial capitalism. Even during moments when unions became pragmatic about including Black labor—a significant move away from outright exclusion—white trade unionists maintained hierarchies of leadership and marginalized the antiracist demands and voices of Black workers. In the hands of white labor, “emancipation” became a tool for rejecting Black people’s unresolved political struggles for Black liberation.

American unions originated within a political economy that married industrial capitalism to plantation slavery. Enslaved artisans once dominated the skilled trades not only in the South, but also as far North as New York City. Planters hired their property out to white industrialists at prices far below the wages of white artisans. White unions emerged correspondingly to exclude Black labor. Though Black people today are more likely than any other demographic group to join unions and while several contemporary unions are Black led, we maintain that some of the first unions were born as anti-Black institutions.

When, after the Civil War, the formerly enslaved began to argue that they were being excluded from unions, white labor undercut those claims in three ways. Archival data reveal, first, that they deployed a “successor discourse.” White trade unionists claimed that since the North’s victory had abolished slavery, addressing white labor’s industrial servitude was the primary struggle, the proverbial next frontier. Next, white labor dismissed Black labor’s critique by homogenizing all workers’ experiences, as if European immigrants and the formerly enslaved shared the same condition. Finally, and on other occasions, white labor deployed a discourse of “possession,” maintaining that if white labor did not organize and thereby control Black labor, white workers would be defeated in labor disputes and labor market competition. While this position was a progressive break from the past, it bound the pragmatics of inclusion with the anti-Black logic of captivity.

By addressing the question of interracial solidarity in this way, the paper makes three contributions. First, we disrupt the either/or logic of the debate in the existing research, which frames unions as either exclusionary or inclusive toward Black people. Second, as an alternative, we advance a novel synthesis of Saidiya Hartman and the sparse but important body of work on the sociology of slavery. Thirdly, we offer empirical grounding for theories of anti-Blackness in the humanities by using archival data on postbellum labor relations.

While making connections between the anti-Blackness of the late 19th century and the fight for a more antiracist and democratic labor movement in subsequent time periods is beyond the scope of our study, future work can draw on our approach to begin to uncover these connections. Scholars may consider how white labor’s refusal to reckon with the afterlife of slavery set the stage for the struggle to desegregate the labor movement in ensuing decades.

Future scholarship might investigate which tactics 20th and 21st century white labor may have used to undermine interracial solidarity and how Black labor responded. For example, in what ways does the history of anti-Blackness in organized labor prefigure A. Philip Randolph’s campaign to organize the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters beginning in 1925? Similarly, to what degree did the shadow of slavery frame the efforts of the CIO and Communist Party to organize Black industrial workers in steel, auto, tobacco, and meatpacking in the 1930s? What are the linkages between postbellum Black trade unionism and the so-called “civil rights unionism” of the 1940s and 1950s? Lastly, in what ways have anti-Black technologies infiltrated contemporary organized labor, as workers struggle to make sense of deindustrialization, globalization, a global pandemic, and the resurgence of fascism? These questions and more comprise the horizon for a synthesis of the scholarship on labor, slavery, and anti-Blackness.

Read More

Venus Green and Cedric de Leon. “The Ruse of Recognition: Black Labor in the Afterlife of Slavery” in Sociology of Race and Ethnicity 2024.

Image: Colored National Labor Union via Wikimedia Commons CC-PD Mark