The Good, the Bad, and the Gig Economy

There are good jobs, which have fair wages, security, and a career ladder. There are bad jobs, which have none of these.

And then there are “good bad jobs,” otherwise known as gig work.

Each day, millions of Americans go to work by signing into an app that algorithmically controls their tasks and sets the price of their labor. There are no coworkers to compare themselves to, no promotions to compete for, and no bosses to please. They cannot manage their bosses or subordinates because they exist outside an organizational structure. Many scholars, myself included, have studied the disadvantages that workers experience in this digital space, with some characterizing platform-based gig work as the ultimate form of exploitive capitalism. And while it’s true that many workers are in the gig economy out of necessity, there are also many who are in it out of choice. They want the schedule flexibility afforded by working outside the bounds of a traditional 8-to-5.

This contradiction has given rise to what I call the “good bad job.” Gig work has elements of both because algorithmic management has changed the social contract between workers and firms. Yes, workers have more choice especially as it relates to schedule flexibility. And at the same these choices are rather limited and are presented among a set of bad options.

Taking Back Control

I spent the past eight years studying the ride-hailing industry, including spending time as both a rider and a driver to gain firsthand knowledge of the work. My research has yielded a number of observations about how drivers keep themselves engaged through workplace games, how they resist the demands of customers and the platform, and how they exert control over their work activities. While all these findings add to the emerging literature on the gig economy, perhaps one of my most significant takeaways is on how algorithmic management systems manufacture consent. I examine this more closely in my recent article, “The Making of the ‘Good Bad’ Job: How Algorithmic Management Manufactures Consent Through Constant and Confined Choices.”

In a workplace, consent can be defined as workers’ willing cooperation with the goals and objectives set by management. Often managers and co-workers help make sure that workers achieve these goals whether if by dangling carrots, threatening sticks, or just plain ol’ peer pressure. Of course, these mechanisms aren’t available in highly decentralized, remote contexts such as gig work. Moreover, algorithmic management is markedly different that other management systems in that it segments the work at multiple sites of human-algorithmic interaction. While small, these segments allow workers to exercise choice over their work activities in the digital world and generates workers’ consent. I identify two tactics: engagement or deviance. A brief explanation follows:

Engagement tactics – With engagement tactics, drivers work with the algorithmic management system, using information from the apps to make decisions about how to navigate within its boundaries. In simple engagement tactics, workers follow algorithmic nudges, such as driving toward high-demand areas, or chasing high-demand (aka surge) pricing begins to obtain a higher fare price. Other drivers accept all rides regardless of the customer rating, figuring they will make up the fare difference through volume.

In complex engagement tactics, workers do not follow the algorithmic nudges; instead, they use information provided by the nudges to inform their navigation of the work. Examples of this include avoiding high-traffic areas so they don’t have to compete with other drivers, or only accepting fares that keep them in a certain location drivers deem most profitable.

Deviance tactics – With deviance tactics, drivers try to get around the algorithmic management system’s directives by manipulating their input into the work-matching, pricing, and ratings algorithms and, if penalized, counter any sanctions from the algorithms. In simple deviance tactics, drivers circumvent the blind matching algorithms that matches with customers by selecting and screening rides. In complex deviance tactics, drivers try to influence their position within the algorithmic management system such as by inflating surge prices or by artificially increasing their acceptance rates.

If the system detects these deviance tactics, it sanctions drivers. But because the penalties are applied in a consistent manner, drivers can consistently counter them.

Whether drivers deploy engagement or deviance tactics, the results are doubly rewarding. Workers feel a sense of mastery and control, seeing themselves as skillful agents rather than just cogs. And even if drivers aren’t following the algorithmic management system’s nudges exactly, they remain online, which is what the ride-hailing company ultimately wants to signal to customers that drivers are available “on-demand.”

The Future of Work

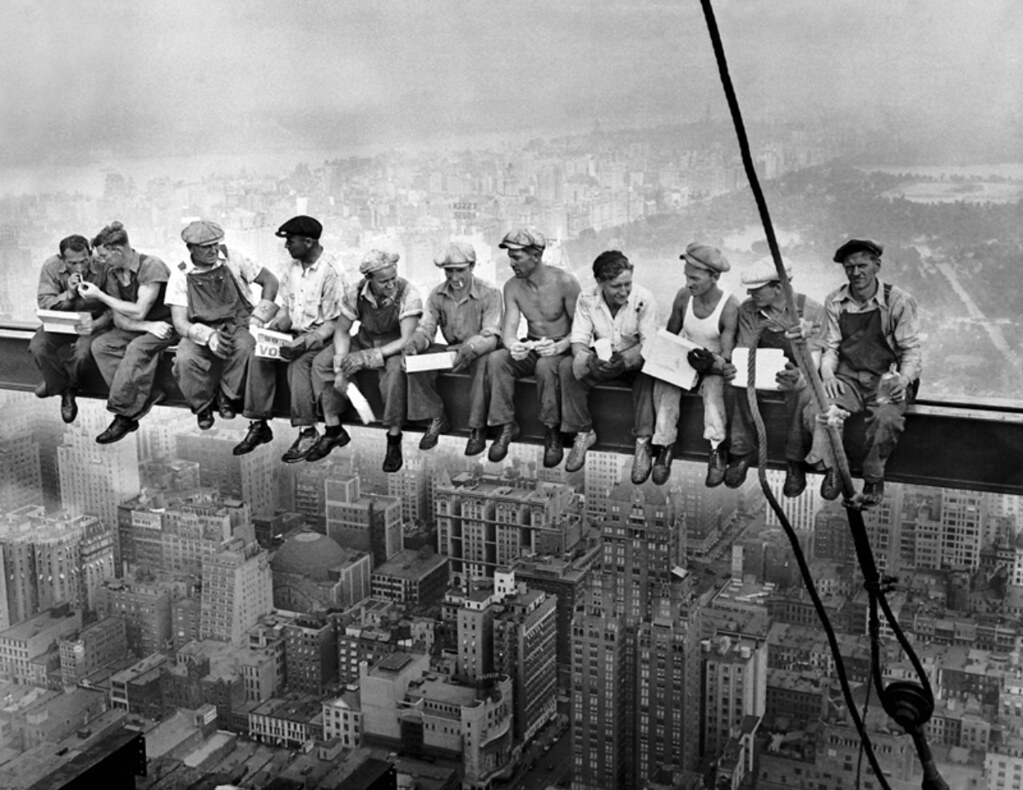

While a lot has changed since I first began collecting data for this research in 2016, one thing hasn’t: The gig economy is continuing to grow. More research is needed to understand the relationship between consent and technology-mediated management, because the labor market is transforming. This isn’t your grandfather’s factory job let alone your mother’s rise through the corporate ranks. Gig jobs are largely asocial and transactional. Algorithmic management obscures workers’ practical terms and conditions are obscured to workers. And there’s little opportunity for workers to foster loyalty, community, or duty to anyone but themselves.

With more and more workers finding themselves beholden to opaque algorithmic management systems worker vulnerability increases. Yet these bad jobs are experienced by many workers as good, insofar as they offer them opportunities to act as agents, especially through deviance and engagement tactics. Legal and policy debates over how to hold these platforms accountable and how to classify gig workers will continue, and I urge those decision-makers to pay closer attention to the behavioral aspects of labor relations. Because it’s clear that the “good bad job” is here to stay.

About the Author

Lindsey D. Cameron is an Assistant Professor of Management and Sociology (by courtesy) at the Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania. She is also a Faculty Fellow at Data and Society Research Institute and a former fellow (member) at the Institute for Advanced Study. Her research interests include algorithmic management, the gig economy, the future of work, and financial well-being. Her research has been published in Administrative Science Quarterly, Organization Science, Journal of Applied Psychology, and Organizational and Human Decision Processes, among others.

Read More

Cameron, L. D. (2024). The Making of the “Good Bad” Job: How Algorithmic Management Manufactures Consent Through Constant and Confined Choices. Administrative Science Quarterly, 69(2), 458-514. https://doi.org/10.1177/00018392241236163

Image credit: Daily Sunny via Flicker Creative Commons (CC by 2.0)