Many people have an opinion about the importance of birth order. They might recall that while their parents gave them a curfew, that didn’t apply to their younger brother. Or that their parents idolized the oldest child. The interesting thing is, research suggests that birth order actually does influence the long-term paths that people follow in life.

Previous research has shown that, compared to first-borns, later-born siblings in the same family tend to have lower grades in high school, are less likely to go to university, achieve a lower overall level of education, have less prestigious occupations in adulthood, and also make less money.

Furthermore, it is not just a difference between first-borns and all later-born siblings; the second-born typically does worse than the first-born, the third-born does worse than the second-born, and so on. These patterns are observed amongst children who grew up in the same family, and can be seen across families of all sizes.

In our study we wanted to extend this research to see whether there are birth order differences in what siblings choose to study if they go to university. College major can matter a lot for long-term outcomes.

Research in the United States and Norway has shown that the difference in long-term earnings between the most lucrative and the least lucrative college major can be as large as the earnings gap between those who go to college and those who do not.

Examining whether there are birth order differences in college major would help us to further understand the effects of birth order on education. Furthermore, birth order differences in college major might explain part of the long-term birth order differences observed in occupational prestige and earnings, given the importance of college major for those outcomes.

To address this research question, you need great data. Fortunately, we had that. We had information on the full population of Sweden, and we were able to link siblings with the same mother and father.

We were also able to link information not only on what major individuals graduated from college with, but what major they applied to study at university. Even more amazingly, we were able to link that information to what happened after university – what jobs people had, and how much money they were earning.

The results from our analyses showed large birth order differences in college major in both the application and the graduation data. For example, we found that first-born children were more likely to study medicine, engineering, and life sciences, while later-born siblings were more likely to pursue programs in journalism, business, and art. These patterns were independent of high school grades, meaning that it was not just a question of prior academic ability or performance.

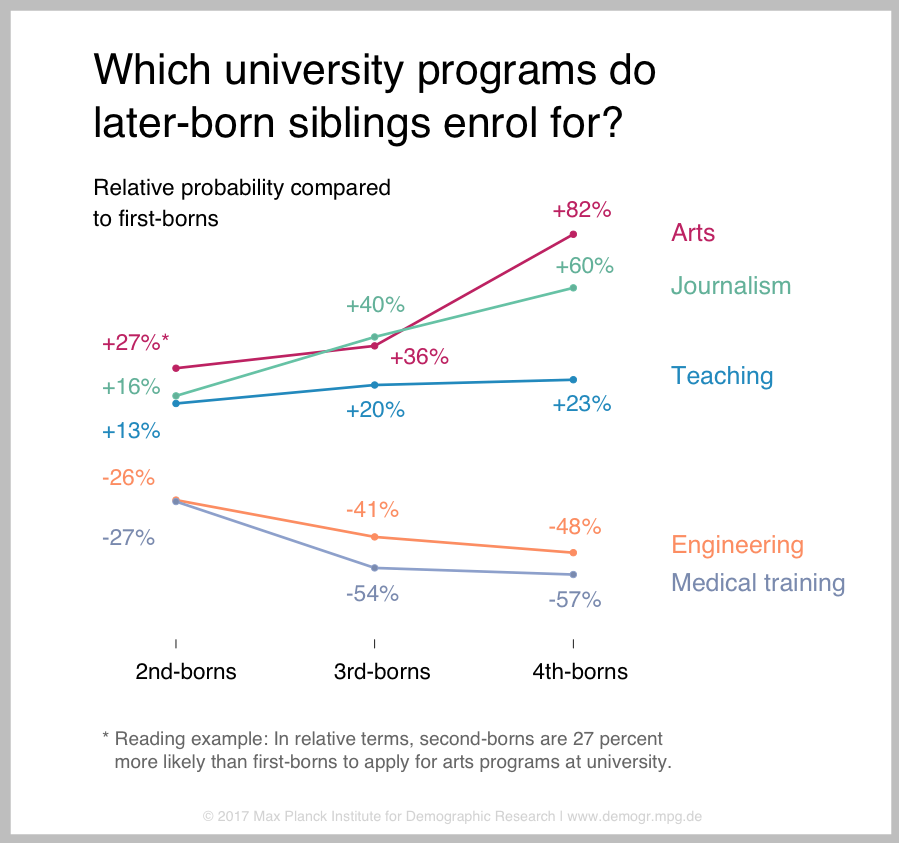

The graph below gives an indication of the scale of the differences. For example, second-borns were 27% less likely than first-borns to apply to medical programs, and the difference between first-borns and third-borns was 54%.

To give another example, second-borns were 27% more likely than first-borns to study arts programs, while the difference was 36% between third-borns and first-borns.

Overall these birth order patterns in college major were much stronger in families with high socioeconomic status than in families with low socioeconomic status. We also found that college major explained approximately half of the birth order differences in long-term earnings.

Since we also observed these differences in applications to university after adjusting for high school grades, our results reflect differences in academic preferences between siblings.

This is fairly astonishing given that our analyses compared children with the same mother and father, and suggests that something about the way that parents treat their children differently by birth order produces substantial differences in academic preferences. The surprising part is not that siblings are different – everybody knows that – but that birth order seems to exert such a systematic influence.

While the data we had access to was extraordinary, we were limited in our ability to explain these patterns. Since the college major differences weren’t a consequence of birth order differences in high school grades, what was driving the patterns?

For the time being we can only speculate. We do know that first-borns have the exclusive attention of their parents when they are the only child in the household. It stands to reason that in the first year of life a fourth-born child would get less attention than a second-born, simply because the parents have less time for each child when there are four kids instead of two. A head-start in development, resulting from a higher level of parental attention in early life might add up to a lot in the long-run.

We also considered the possibility that parents impart knowledge about their own educational experiences to their children, and that this might vary by birth order. However, our attempts to check this empirically did not show any meaningful birth order differences in terms of studying the same subject as the parents.

Although the children of doctors are more likely to become doctors than the average person, the first-born child of somebody who studied medicine is not more likely to study medicine than the second- or third-born sibling.

There is also empirical evidence that suggests that parents treat their children differently by birth order. Although parents tend to report that they treat all their children the same, the children know otherwise. Furthermore, independent observers tend to corroborate the children and not the parents.

For example, mothers are more likely to breastfeed the first-born child than later-born children. They are also more likely to seek prenatal care for the first-born. In Sweden, parents take more parental leave for first-born children. In the US, parents restrict TV watching to a greater extent for first-borns than later-borns, and are more likely to punish first-borns when they get bad grades in school. Although we do not know whether these kinds of differences in parental treatment are driving our results, it is certainly a possibility.

Although differences in parental investment between families are typically much greater than the differences within families, our study indicates that these differences within families play an important role in the formation of preferences as well as long-term socioeconomic attainment. While most scholars and policymakers focus upon differences between families, the within-family variation clearly also deserves attention.

No Comments