People who earn post-secondary degrees have better lives than those who do not. They get better jobs, earn more money, are healthier, happier, and are more civically engaged.

People who earn post-secondary degrees have better lives than those who do not. They get better jobs, earn more money, are healthier, happier, and are more civically engaged.

In the popular imagination—and research literature—it is through education that people from poor backgrounds improve their socioeconomic status. Education is an essential part of the American meritocracy.

If you want to improve someone’s life, send them to college!

But everyone involved with higher education—and a large number of people outside of it—are aware of college graduates who are underemployed, or working in relatively low-skilled jobs. Jokes aside, about humanities majors working in restaurants, anyone who spends time around young adults knows some who struggle to find work commensurate with their education.

In a recent study, I found that more recent cohorts of college-educated adults are struggling to find high-skilled jobs. There are too many college graduates for too few skilled jobs.

The Expansion of Higher Education and the Value of a College Degree

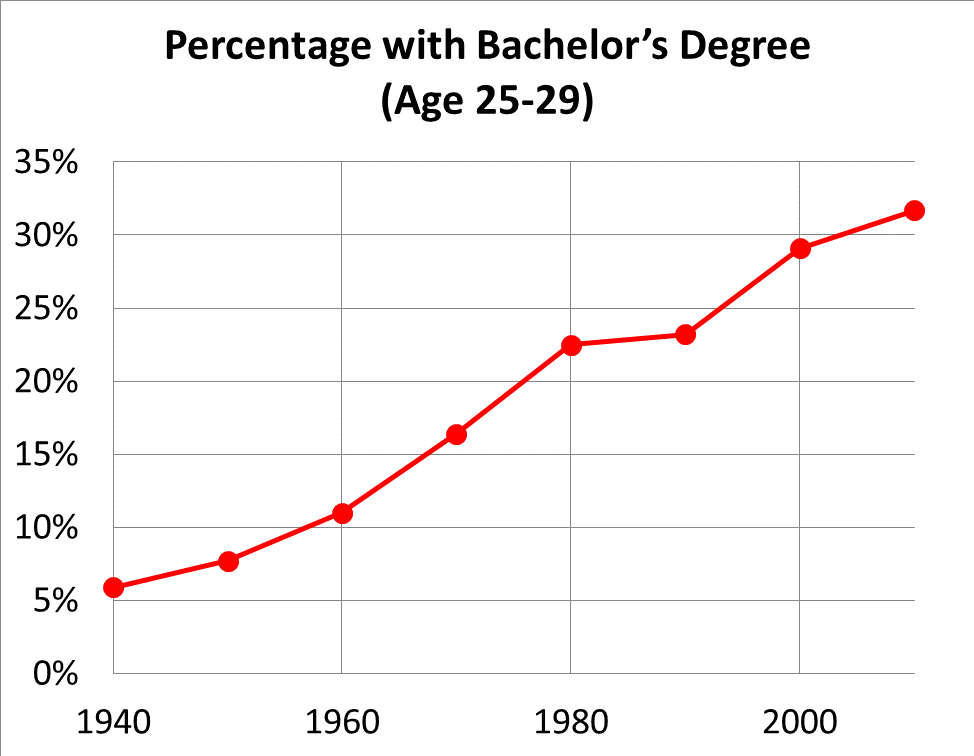

Due to substantial investment in higher education in the twentieth century—and widespread recognition of college’s benefits—college completion rates quintupled between 1940 and 2010.

Source Data: Digest of Education Statistics 2016, Table 104.20

Unfortunately, there aren’t enough high-skilled jobs for all of those college graduates.

Based on three measurements of occupation-level skill—quantitative, verbal, and analytic skill utilization—I found that as college completion rates rise, college-educated workers are landing less-skilled jobs across all three domains. I derived these skill scores—measured in continuous “points” from approximately 0 to 6—from O*NET ratings from the early 2000s. These scores are publicly available at SocArxiv.

To demonstrate the magnitude of these changes, I predict the value of a college degree in a world where 8% of your cohort has a bachelor’s degree versus a world in which 40% of your cohort has a bachelor’s degree.

The changes in skill-utilization are mostly moderate, but noticeable. For example, men with a bachelor degree get less verbally-skilled jobs, and the difference is equivalent to the difference between a librarian and a clergy member.

However, one effect is large: Men with a bachelor’s degree land substantially less analytically-skilled jobs (0.45 points) as college education rises. A difference of 0.45 points in analytic skill is roughly the distance between an actuary and a middle-school teacher.

While higher education expansion has a deleterious effect on those with a bachelor’s degree, it has no negative effects on workers with no college experience. In fact, if anything, there is a marginal increase in skill utilization for workers with no college experience in the period of college expansion.

The result is that the advantage of a bachelor’s degree over those without any college experience declines by substantively large amounts as higher education expands.

These findings are somewhat unexpected, since the dollar return to education has gone up dramatically in recent years. If people with bachelor’s degrees land lower-skilled jobs, why are they also being paid more money?

This a puzzle that is beyond the scope of the present study. One possibility is that the college-educated workers in finance—or other increasingly highly-paid professions—are making so much more money than in earlier eras that it is outweighing those who cannot get skilled work.

What do we do about this?

Going to college is a good idea. It likely remains the best way for a person from a poorer background to move into a higher socioeconomic bracket. Plus, people who earn a college degree have better lives than the people who do not.

But sending groups of people to college without any other intervention has unintended consequences: It increases competition enough to substantially erode the power of a college degree in the labor market.

Worse, because the bachelor’s degree loses its power in the labor market, a new race begins to earn master’s degrees. Using degree completion as an anti-poverty measure promises an education arms race, where young adults must attain even more credentials to stay ahead of their peers. In this arms race, it is likely that affluent young men and women continue to hold a better position.

The problem is that restricting the number of overall college slots across all institutions is not a good response. It is difficult to promote access for poor high school students to attend college while simultaneously restricting the number of slots available.

Moreover, as Emily Rauscher points out, increased education in the population can actually create more good jobs, although clearly not fast enough to compensate for the increase in educated workers. Furthermore, research conducted at universities has beneficial effects on the economy. Restricting higher education does more harm than good.

There are three possible solutions to prevent an education arms race, maintain the value of a college degree, and reduce inequality in the United States.

- Fund Affordable, Accessible, High-Quality College Education: Recently, low-quality education programs have expanded. These programs do not effectively educate their students and do little to promote social mobility. Much of the focus has been on for-profit colleges, but many not-for-profit colleges have expanded what Tressie McMillan Cottom calls “Lower Ed.” I strongly agree with Cottom that many so-called “problems” with higher education are actually dysfunctional labor markets and a similarly dysfunctional social contract. However, if we are to realize the macroeconomic benefits of high human capital—as Rauscher suggests is possible—we need to make sure that higher education actually provides human capital.

- Investment in More High-Skilled Jobs: The present study shows that there is unlikely to be a shortage of skilled college graduates, as the declining value of a college degree is a symptom of not having enough highly-skilled jobs. There are a large number of college graduates available for industry, and increased public support for research initiatives at universities can help generate skilled jobs. If industry does not want them, perhaps it makes sense to expand the public sector to take advantage of the labor surplus.

- Make Bad Jobs Better: We pin a lot of hopes on the education system to fix inequality. But the education system cannot address the problem of “bad jobs”—jobs that pay poverty-level wages and provide limited benefits. Suggesting that education can lift some workers out of poverty ignores the fact that others are still in bad jobs, and inequality remains stable. To fix inequality, “bad jobs” must become better—perhaps by increasing the minimum wage—or we should improve the social safety net to compensate for the poor pay and benefits at bad jobs.

1 Comment

It’s disappointing that Mr. Horowitz reached the conclusion he has–that we should continue to expand the volume of the college educated. Education–or specifically the college/university degree–has become a commodity. It’s value depends on the relative availability of the commodity. Now that college degrees have become commonplace, they simply aren’t worth much. For those who win the higher-skills/higher-pay/more-benefits lottery, indeed their college degrees seem to have been a good investment. But this comes at the cost of growing poverty among many of those promised an escape from poverty through education. This wouldn’t be so grave a problem if, as in other investments, graduates could declare bankruptcy if after many years attempting to capitalize on their degrees they demonstrably failed. But as we all know, the US has made it extremely difficult for graduates to escape destructive education-related debt. Many graduates are worse off having completed their multiple degrees than if they’d invested the time elsewhere.

Yes, Mr. Horowitz is right that we ought to increase the number of “good jobs” AND improve either the social safety net that compensates those stuck in “bad jobs” OR drastically improve the conditions of “bad jobs.” But these things aren’t likely. For one thing, as recent economic reports from the US show, despite harrowing financial conditions for millions of citizens due in part to the pandemic, US corporations posted record profits. This has been happening for decades–increasing corporate profits despite largely stagnant inflation-adjusted wages for the bulk of workers. After the recession of 2008, most of the jobs that returned to the US market were “bad jobs.” Companies could have created more “good jobs,” but the ubiquitous profit motive together with other factors favor fewer “good jobs,” not more.

Interestingly, where companies claim graduates lack the skills companies are seeking (so-called high tech skills), companies still refuse to offer job-training to the army of bachelors and masters prepared bright, willing job applicants. Companies continue to demand that applicants shoulder the costs and uncertainty of skills acquisition, problematic when in vogue tech skills evolve quickly and the skills particular industries demand are often job-specific. It would be more efficient to TEACH bright, capable applicants exactly what the employer wants instead of waiting for graduates to pay thousands more to tech-training bootcamps in hopes they’re learning the exact tech skills jobs they have yet to apply for will demand.

Nor does the recent political climate in the US bode well for improving the social safety net. Abundant research, for example, points to housing insecurity as a primary factor driving poverty and poor physical and mental health. Yet housing costs continue to soar in the US while the US government itself confirms there is not a single US zip code with sufficient affordable housing. If we won’t or can’t even provide our citizens one of the most fundamental survival requirements, it’s unlikely we will adequately address workers’ rights attrition or poverty-wages or other conditions underlying “bad jobs.”

Mr. Horowitz, like so many other academics, is too optimistic in his assessment of what our political and corporate leaders are willing to do. I’m reminded of health care corporations demanding the government grant them immunity from negligence law suits during the pandemic. And of other corporate leaders advising companies “struggling” with a paucity of job applicants for available (largely bad) jobs to be patient and NOT offer higher wages because US workers would soon run out of savings and, desperate for survival resources, return to the jobs market. Education should not be THE path out of poverty. A country as wealthy as the US ought to do vastly more to expunge poverty FOR ALL CITIZENS. Otherwise, those who can’t, for many valid reasons, pursue “higher” education will remain condemned to poverty. Moreover, those among the growing percent of the population heavily financially invested in college and university education will join the unfortunate former since the competition to get the few good jobs will just become more and more fierce. But the academic studies put forth refuse to acknowledge this, instead almost invariably choosing to view the circumstances through rose-tinted glasses. Both disappointing and dangerous.