We often hear pleas for frank discussions about “race in America.” Yet rarely are Asian Americans ever seriously considered in this supposed dialogue. The important history and notable socioeconomic achievements of Japanese Americans, for example, are typically entirely ignored. If Japanese Americans are considered at all, then usually they are naïvely portrayed as the spineless victims who got interned during World War II but who are otherwise insignificant for understanding “race in America.” See for example, Race in America by Desmond and Emirbayer who even refer to the Japanese American internment as the historical origin of “The Prison Boom” even though those internees were never charged with any crime much less convicted of one.

Ignoring the socioeconomic circumstances of Asian Americans was once possibly justified on the grounds that they were such a small demographic group. In recent decades, however, the population of Asian Americans has been rapidly increasing. In percentage terms, they are now the fastest growing racial category. Asian Americans have become ubiquitous in many professional occupations, elite universities, media outlets, and notable artistic and cultural organizations. They have often been known to be superlative leaders in business, government, athletics, and the military.

Yet contemporary American sociology, like some of the general public at large, continues to be ill at ease in accepting Asian Americans as a mainstream group to consider in the national dialogue on racial relations. This reluctance may arise because Asian Americans are a non-white minority that appears to be at odds with popular liberal views about a “racial hierarchy” which is said to foster “white privilege.”

The typical liberal discourse on “race in America” is generally framed as purporting to promote the liberation of oppressed non-white minorities from the evils of racial discrimination. But this mantle is a bit awkward to promulgate in regard to a group like Japanese Americans who traditionally have had lower poverty rates than whites as well as higher levels of educational achievement, per-capita household income, and occupational attainment.

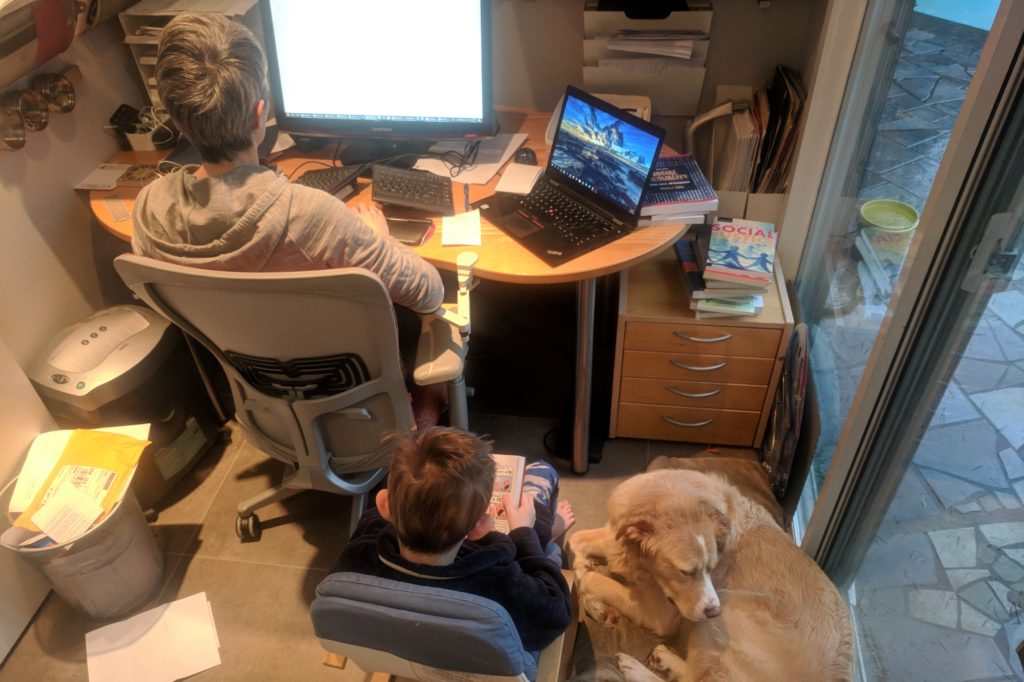

For many families, integrating work and care remains a challenge. Is flexible work the answer? By affording workers greater freedom to organize their jobs in ways that suit their lives, flexible hours and the ability to work from home can help parents meet children’s needs while still getting their work done.

For many families, integrating work and care remains a challenge. Is flexible work the answer? By affording workers greater freedom to organize their jobs in ways that suit their lives, flexible hours and the ability to work from home can help parents meet children’s needs while still getting their work done. Forget the red roses and teddy bears this Valentine’s Day – the best way for men to shore up their relationships is to run the vacuum over.

Forget the red roses and teddy bears this Valentine’s Day – the best way for men to shore up their relationships is to run the vacuum over.

The decision to become a stay-at-home parent is often not easy – many parents weigh the costs of career sacrifices relative to the benefits of increased family time. They might want to consider another cost: how easy will it be to return to work?

The decision to become a stay-at-home parent is often not easy – many parents weigh the costs of career sacrifices relative to the benefits of increased family time. They might want to consider another cost: how easy will it be to return to work?